Early last week, a list appeared – Pitchfork’s The 50 Best Ambient Albums of All Time. As it began to do the rounds, I was surprised. Ambient music didn’t seem like the magazine’s forte. In the last few years, there’s been a surprising growth of interest in the genre – one small element of a larger cultural reappraisal of the history of recorded music, bringing to light thousands of albums once thought lost to the shadows of time, and in the case of Ambient, reigniting it as a relevant contemporary pursuit. As a fan, I was naturally curious about what Pitchfork had to say. As a fairly serious record collector, I tend to offer these lists a suspicious eye – particularly because most seem to conceived as click bait and content filler, rather that offering their subjects the attention and thought they deserve. I bit the worm. Upon entry, I was startled to find myself faced with Keith Fullerton Whitman’s words. Things were looking up. Keith is a remarkable musician – one for whom I carry a deep respect (the only in memory, to make my ribs noticeably vibrate with ecstatic joy). He’s also a serious collector, runs a record shop, and carries an astounding a wealth of knowledge – arguably unparalleled in the fields of Electronic and Ambient music. There’s no one better to pen such a list. This was going to be good. My heart skipped. Excited, I wondered if this was to be the Ambient equivalent of Thurston Moore’s Top Ten From The Free Jazz Underground, Alan Licht’s Minimal Top 10, or those lovely lists Jim O’Rourke squirreled away. The hope was short lived. Keith had only written the introduction. Things plummeted downward from the beauty of his words.

Keith Fullerton Whitman – Generator 1, from Generator (2010)

The problems with Pitchfork’s list were many and few. Most issues could have been resolved by abstaining from the publication’s chronic disposition toward grandiose and misleading titles. Had they simply called it, Pitchfork Writers Pick Their Favorite Ambient Albums, you could have let it off the hook. At least then you could account for the subjective view. During the days following its publication, social media was set a blaze. Everyone had an opinion, and rightly they should. The list established no ground on which to stake its claim, was lazy, and knew little of its subject – in cases, even misrepresenting it. It was effectively the opposite of what it set out to be. You could say that all lists which attempt to be definitive, are damned to fail. No one knows everything, while opinions are more than a few. The best you can do is account for yourself. This list is particularity bad. The issue isn’t the albums and artists chosen for inclusion, or the affection and quality of each writer’s approach. It’s the misleading nature of the whole. What it displays, is not what it claims – and for that, as in all cases of journalism, Pitchfork and its editors, must bear the weight of blame.

The chatter went on. First The Stranger issued issued a rebuttal – Dave Segal’s We Give Pitchfork’s 50 Best Ambient Albums List a 6.7. Here Are Some Glaring Omissions, which, recognizing he was filling in gaps, makes a pretty nice list on its own. Then came Self-Titled’s – #not the best ambient albums of all time, penned by Rafael Anton Irisarri, with an accompanying list – largely focused on post 2000 artists. Also nice. In both cases, the authors displayed a far better understanding of their subject than the source of their ire, while offering greater context and entry for their readers. In each, I was equally surprised by what they missed.

These lists – whether bad of good, occupy a fascinating place in cultural discourse. In many ways, you have to thank them all. Even in failure, they open conversation and debate. Because Pitchfork gave 50 albums, Segal gave us 50 more, and Irisarri waded in with yet another 100. That’s a beautiful thing. I don’t know who – if any, sculpted what will come to be seen as the definitive group. It almost doesn’t matter. Each album and artist mentioned is worthy of attention and praise. For my part, aware that a great deal had been missed, I wondered if I should wade in. In the grand scheme of Ambient music, I don’t assume to know much. It’s a passion bubbling below other passions. I could certainly make a list of my favorite hundred beauties or more, but Pitchfork, Segal, and Irisarri, had jointly mentioned many of the greats.

Record lists are rarely the revelation they were in my late teens – when Moore and Licht’s “top tens” first emerged. My hope for them remains, though rarely fulfilled. Those early efforts entered a different world. Change has birthed new challenges. I’ve since spent many years with my fingers in the bins. The albums they mentioned where discovered through deep passion and rigorous search. At that time, they had largely been lost from view. Importantly, at least for this writer, those lists were generous and seemed to achieve what they set out to do. They changed the course of my pursuit, and sculpted the way I believed one’s knowledge and discoveries should be shared. Neither Moore nor Licht were attempting to make a definitive statement. They were simply offering records to dig – ones they though were worthy of more attention than they’d ever received. Beyond luck and chance, it was nearly impossible to uncover these albums on your own. I remain deeply grateful. Of course the internet, blogs, streaming sites, endless reissues, and even Youtube, have changed all that. What once took years in the bins to discover, can be found without leaving your home. What strikes me about most contemporary lists, is that they tend to take a position of authority, but rarely plumb the depths beyond what’s now easily to hand. All three of those mentioned above, though containing remarkable works, drew heavily on albums which have been issued, or reissued, in recent years. They are part of an easily accessible sphere of knowledge. With the help of Google, curiosity and drive, most listeners could find them on their own. The crucial thing, which both Licht and Moore proposed, was the joy of discovery and the hunt – that history held amazing treasures, waiting to be found. When considering what to choose for what to include in my own approach, this seemed like an essential factor. In the era of the internet, with so much at hand, how could I carry the spirit of the lists which had once changed my life?

The Hum’s Nine Essential Picks

For days I pondered. I wracked my brain. What would I include? I could fill in the gaps, but without those already mentioned, would my entries make a great list on their own? Would such a selection allow for an accurate vision of what I hoped to display? Given that I write more than most, economy was a concern. I had to limit myself to ten albums or less. For that, a list of favorites was the first to go. There would be too much overlap, while without those already mentioned, too little to give an appropriate view. I decided to construct an ideal group (regardless of overlap), and move along. The image above contains my hard fought essential picks – Iasos’ Inter-Dimensional Music, J D Emmanuel’s Wizards, Edward Larry Gordon’s (Laraaji) Celestial Vibration, Ariel Kalma’s Open Like a Flute, Hiroshi Yoshimura’s Green, Michael Stearns’ Planetary Unfolding, Steve Roach’s Structures From Silence, Don Robertson’s Celestial Ascent, and K. Leimer‘s Closed System Potentials. Believe me, I could go on. I’ll probably kick myself for settling where I did. That said, not only are these among my absolute favorites, they were also chosen to attempt to offer new listeners entry into some of the best of what the genre has to offer, while hoping to represent as diverse a number of approaches as I could. There are plenty of places to go from there. I leave that to you – at least for now.

My second thought was to explore the more obscure depths of the New Age movement – albums difficult to unveil from the shadows of history. Truthfully, others could do it better than I – particularly Will from Sounds of the Dawn. His knowledge is second to none. I’d rather wait for him to show his hand. I briefly considered the strange ambiences of electroacoustic and electronic pioneers, but again it wasn’t a fit. Finally it hit me. I should make the list that few others could (or would). A digger’s list of under-recognized gems – singular works, sitting somewhere between the avant-garde, and the larger bodies of Ambient and New Age music. Those which defy easy categorization, and thus fall through the cracks. The criteria was simple – albums that represent the particular character of Ambient music’s incongruous roots and diversity of practice, which haven’t been reissued in recent years, and are almost never mentioned, if at all. My choices are obscure, but certainly not unknown. These days, I make no claims. I’m not the first to bring them into view, simply the one to gather them in such a way. In the spirit of discovery – as it was once proposed by figures like Moore, Licht, and O’Rourke, these albums deserve far more attention than they would otherwise receive. The added benefit of this choice, and underlying conceit, is that most of these albums, because they have thus far remained largely out of view, are currently affordable and available (all but three generally sell for below $20). Crucially, I hope these selections will offer discovery for well seasoned listeners, as well as those new to the field.

As with many musics, the roots of Ambient music grew from the Avant-garde. The genre’s defining characteristic is a shift away from the emphasis on standard musical structure and rhythm, while placing greater attention on tone, harmonics, and atmospheric sound. Though we all have our associations attached to what we assume it to be – dreamy passages of synthesizer music, it encompasses a great deal more. Ambient music has three distinct roots. The most cited are Minimalists like La Monte Young, Charlemagne Palestine, and Terry Riley, who drew a great deal of influence from Indian Classical music – particularly the use of drone and the ambient overtone harmonics generated by the rapid repetition of notes on instruments like the santoor. In fact, there were others earlier still. Artists associated with Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRM) – Pierre Schaeffer, Guy Reibel, Luc Ferrari, François Bayle, etc, began composing music which deemphasized standard structures, and utilizing resonate fields of ambience, during the late 50’s and early 60’s. They were soon followed by the more refined visions (to this end) of Michel Redolfi and Eliane Radigue. In America, there were also roughly concurrent efforts made by figures at the San Fransisco Tape Music Center – particularity Pauline Oliveros, and by members of the Sonic Arts Union – Robert Ashley, David Behrman, Alvin Lucier and Gordon Mumma. This settled, it’s important to not confuse Ambient pioneers, with the movement itself, which takes these early leaps one step more.

Structure is impossible to avoid. Even what claims not to be, becomes that thing in time. Though each of the figures mentioned above proposed new forms of harmonic possibility, it’s important to recognize that the object of their music and tones generally maintained autonomy from the listener. Ambient music attempted to dissolve this divide. It proposed a kind of sonic space which the listener could enter, or could entered the listener in specific ways (as in the case of Healing music, etc). It’s objective was to construct a sonic realm in which harmonic ambience would supersede the notes which generated it, and thus dissolve the music’s allusion to physicality, with the standing architectures of a listener’s relationship to it. The differences may appear subtle to the ear, but they exist. This is why the piano works of La Monte Young and Charlemagne Palestine, which share many characteristics with Laraaji’s approach to the zither, are in fact another thing. Their structures do not entirely dissolve within a primary harmonic field. One is to listen, the other is to enter.

With some context for entry, I give you my list of obscure gems from the Ambient world. Each was chosen through affection, but also because they represent a strange link between the avant-garde and the places where ambient music is usually though to reside. They don’t fit anywhere well, which may explain their neglect. Each holds a treasured place in my collection. May this be the end of a condition, which makes them obscure – and may they remind you of the beutiful spirit found in the hunt.

Mother Mallard’s Portable Masterpiece Company – Mother Mallard’s Portable Masterpiece Co. (1973)

Mother Mallard’s Portable Masterpiece Company is probably this list’s most well know entry. This album has long resided in a hallowed place for collectors of avant-garde and experimental electronic music. Surprisingly, I still don’t hear it come up much. The ensemble was formed in 1968 by David Borden, Steve Drews and Linda Fisher in Ithaca, New York, with the help of Robert Moog. They were among to the first to apply the ideas of Minimalism to synthesizers – utilizing both repetitive rhythmic patterns, drone, and reduced washes of sound. In the process, they helped define Ambient music’s coming sound. Their self-titled release is not an exclusively ambient work. It shifts between wild moments which are structurally reminiscent of Steve Reich and Terry Riley, and moments of pure ambience (particularity on the second side) which foreshadow the coming New Age Movement. Any way you look at it, and whatever you call it, it’s a remarkable piece of work – sounding as weird and fresh today, as it did when it was made.

Mother Mallard’s Portable Masterpiece Company – Mother Mallard’s Portable Masterpiece Co. (1973)

Stuart Dempster – In The Great Abbey Of Clement VI (1979)

How history has missed Stuart Dempster, I have no idea – particularly with the towering brilliance of 1979’s In The Great Abbey Of Clement VI. This work is an unheralded masterpiece. It should be in the collection of every fan of Minimalism and Ambient music. Dempster is a trombonist and composer, who for many years collaborated Pauline Oliveros. Together with Panaiotis, they founded the iconic the Deep Listening Band. In The Great Abbey Of Clement VI is a solo work for trombone and plastic sewer pipe. After that, I shouldn’t need to say more. It’s an astounding and stunningly beautiful piece of work, leaving the listener lost in other worlds of shimmering ambience and space. It’s slow, meditative, and altering. Easily one of my favorite records of all time. (For clarity, the album was issued with two covers. The first pressing is above, while the second is featured in the video below).

Stuart Dempster – In The Great Abbey Of Clement VI (1979)

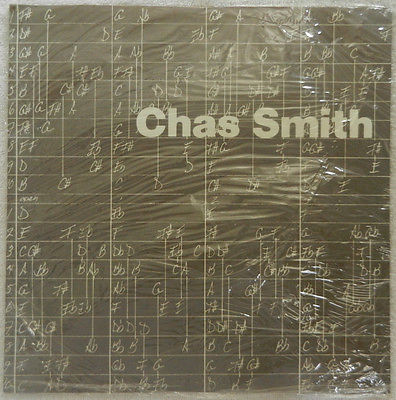

Chas Smith – Santa Fe (1982)

I don’t know much about Chas Smith. He’s an incredible peddle steal player, worked with Harold Budd over the years, and was among the astounding stable of artists issued by Cold Blue. For those unaware of it (I’ve been meaning to write a profile for a while) Cold Blue was a short lived California based label during the early 80’s (recently reestablished), which released seven 10″ records dedicated to a stunning group of West coast composers. They also issued one LP by Daniel Lentz, and an incredible (and still very affordable) compilation which features Harold Budd, James Tenney, Ingram Marshall, among many others. I can’t remember how I came across Smith’s Santa Fe, but it graced the upper tiers of my want list for many years – subsequently introducing me to the larger body of artists on the label. It’s a thing of beauty – at times sounding more like a synthesizer than a guitar. It ripples with ambience, space, and restraint. Definitely an unsung masterpiece, and worthy of the hunt.

Chas Smith – Santa Fe, From Santa Fe (1982)

Frank Perry – Deep Peace (1981)

Frank Perry is a fascinating figure, and not one you would expect to find in the world of ambience. Over the course of his career as a drummer, he’s collaborated with Alan Davie, Keith Tippett, David Toop, Max Eastley, Evan Parker, Paul Kossoff, among countless others. His solo output is another thing. During the early 80’s Perry began releasing albums with heavy New Age themes. Deep Peace is the the first of these. It’s a complex album which shouldn’t be dismissed for first appearances. It occupies a fascinating middle ground between the Tibetan singing bowl recordings you’re likely to hear in hippie shop, what you might expect from a master of avant-garde percussion, and the kind of tonal relationships first displayed within Groupe de Recherches Musicales. It’s brilliant, challenging, and immersive. Though I’ve bought ambient records since my late teens, it was strictly dictated by chance encounter and taste. It wasn’t something I actively pursued. Perry’s Deep Peace changed all that. He opened up this world, and changed my pursuit of the spacial possibility of sound. Perry’s depth and breadth is striking. It immerses the listener in resonances, harmonics, and dissonances which you almost never find in the world of New Age. He pushes the possibilities of ambience into new realms, and defies what we presume to know. This is one of those records that doesn’t deserve to be tied down.

Frank Perry – Deep Peace of the Son of Peace to You, from Deep Peace (1981)

Frank Perry – Temple of Sound, from Deep Peace (1981)

Peter Michael Hamel – Colours Of Time Part 2 (1980)

Craig Kupka – Clouds 1, from Clouds – New Music For Relaxation (1981)

Craig Kupka – Clouds 2, from Clouds – New Music For Relaxation (1981)

Synergy – Computer Experiments Volume One (1981)

Computer Experiments Volume One is a strange one-off endeavor by a fairly prolific studio musician named Larry Fast. During the 70’s and 80’s he worked with everyone from Yes, Peter Gabriel, Meatloaf, Hall and Oats, and Kate Bush, as well as recording Prog opuses under the name Synergy. In 1981 he embarked on a series of experiments with a self-composing computer program – hooked to a modular synth. The result was Computer Experiments Volume One. I have no idea how much control Fast had, but it’s amusing to think that his best album was composed with none of his input at all. Anyway you look at it, the record is fantastic. Harsh droning resonances intertwining, while penetrated by brittle tones. It has all the hallmarks of a classic New Age, but feels bent and fucked – almost as though the dream was going wrong before the computer’s eyes.

Synergy – Artificial Intelligence (Monday), from Computer Experiments Volume One (1981)

Synergy – Artificial Intelligence (Friday), from Computer Experiments Volume One (1981)

Synergy – The World After April, from Computer Experiments Volume One (1981)

Roger Winfield – Windsongs (1991)

Roger Winfield’s Windsongs is an astounding thing of beauty. It’s one of the greatest Ambient albums I can call to mind, and yet doesn’t have the hand of its composer anywhere to be found. Winfield is a member of a very small number of instrument makers whose music is played by the wind. I have one other record by such an artist from the early 70’s. I bought it thinking it was unique take on sound sculpture, and the work of figures like Harry Bertoia. When I discovered Windsongs, I wondered if there were more. It turns out there are. Winfield’s instruments are called Aeolian harps. They apparently have ancient origins in a smaller form, and were incredibly popular during the 17th century – placed in windows to generate harmonic ambience. Winfield’s version of the instrument is on the grand scale. I feel like I remember being fascinated by something similar in Boston as a kid. Truthfully the backstory of little consequence. The sounds speak for themselves, and thus what I’ll let them do. They’re astounding and timeless – resonant harmonics bound within recordings of the wind.

Roger Winfield – North Wind, from Windsongs (1991)

Roger Winfield – South Wind, from Windsongs (1991)

Roger Winfield – East Wind, from Windsongs (1991)

Roger Winfield – West Wind, from Windsongs (1991)

Michel Madore – La Chambre Nuptiale (1979)

Michel Madore is a Canadian artist. To my knowledge he only made two records during the late 70’s. One is decidedly Prog. The other – La Chambre Nuptiale, is fairly singular and defies categorization. It’s amazing. The album is built largely from field recordings, Musique concrète techniques, synthesizers, and organ. The first side displays a lovely hybrid ambience built from modular synths and organ. It’s beautiful, engrossing, and unlike much else I can call to mind. The second side is another beast. It’s unquestionably avant-garde. It sounds like Madore dumped the entire history of sound – as he encountered it, into a blender, and spit out a seething mess – a sonic collage, sculpting a new dark vision of cultural ambience. As a totality, the record is a fantastic piece of work. Definitely an under-recognized gem.

Michel Madore – Les Anges Qui Passent : Dialogue, from La Chambre Nuptiale (1979)

-Bradford Bailey

A nice piece – I sent Frank the link – I think he’ll appreciate it.

LikeLike