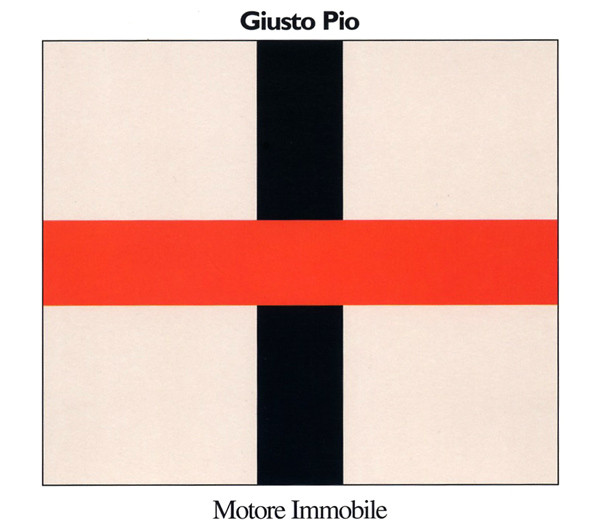

Giusto Pio – Motore Immobile (1979 / 2017)

Somewhere along the way, working on hint and clue, Giusto Pio’s Motore Immobile came back into view. Many encountered it for the first time when it appeared in the third installment of Alan Licht’s iconic Minimalist lists – published in 2007 by Volcanic Tongue (the first two had been published years before by Halana), but I was already hunting by then. Ever elusive, it remained my great holy grail – the number one – a hiding ghost. I wasn’t alone. Initially issued by the legendary Cramps imprint in 1979, for those aware of it, the album is among the most unobtainable, sought after, and cherished releases of the label’s astounding output – the crown jewel of the Italian Minimalist avant-garde.

For years Motore Immobile haunted my dreams – a taunting gap. I longed and waited. At one point I even blindly emailed Fabio from Die Schachtel – begging him to reissue it. I was desperate and couldn’t think of anyone else that would.

Time passed. The longing increased – met by silence. While landscape for reissues ballooned, it seemed that no one was interested in my lost dream. Then one day, not so long ago, Fabio emailed – we’d been corresponding regularly for some time. He had news. A new imprint called Soave was reissuing Motore Immobile. My head swam. My heart skipped. He went on – asking if I’d be willing to contribute a short text for the liner notes. Before me lay one of the greatest honors of my short career – to pay tribute to my beloved holy grail – to take part in its reemergence – to sing its praises from within.

I first drew attention to Motore Immobile in my piece The Obscure Brilliance of Italian Minimalism (In Nine Albums) – an homage to that remarkable movement, through some of its greatest artifacts. Of the albums I featured, it was the only one I didn’t own – making the effort slightly bittersweet – picking at an already open wound. It couldn’t be skipped.

Italian Minimalism was unique – yielding untold depths, in very interesting ways. Beginning later than most of its international counterparts, it was often more restrained, while adding structural and tonal complexity. It took on more with less. While the majority of the broader movement’s practitioners stemmed almost exclusively from the Classical Music world, members of the Italian school came from a diverse number of backgrounds – particularly from rock.

The first wave of Minimalism was more reactionary than most remember. It’s popularity was such, that we often forget it’s Classical Music – intuitively regarding it as unique kind of avant-garde Pop. This isn’t an accident. Its origins sprang from a rejection of the 20th Century’s two previous dominant forms – Serialism, and the music of Chance and Indeterminacy which grew from the ideas of John Cage. Both were known for their slim popular appeal – often sending audiences running – interpreting what they heard as inaccessible, elitist, and opaque. Minimalism took another path. Through the use of pure intervals of perfect thirds and fifths, and in some cases just-intonation, its first composers – Reich, Riley, Young, Glass, embraced structures which where more appealing to the ear – creating an often ecstatic and spiritually infused Classical Music – one accessible to all. Though it began within the avant-garde, as it progressed, it consciously built bridges between formal composition, the blossoming psychedelic underground, and broad public appeal.

Because many Italian Minimalist composers had previously worked within more popular forms of music, their objectives and hopes for their creations were very different. Their movement swam against the prevailing tide. It was less single minded, drew on more diverse influences, and was generally more radical, challenging, counter-cultural, and explicitly avant-garde. Rather than Classical Music, it could be understood as an extreme realization of the momentum begun by bands like Soft Machine, Gong, The Third Ear Band, and a number of Krautrock pioneers, who, believing in their audiences’ potential and abilities, pushed their sounds to new challenging heights. Italian Minimalism often embraced the very optimism at the heart of what their American counterparts where reacting against. Though making equally valuable contributions, and similar in many ways, the two movements where shifting in opposite directions – one toward Pop and the other away – two ships passing in the dark.

Giusto Pio, like many in his generation of Italian musicians and composers, was restless. He was also one of the few prominent Minimalists, whose origins trace to the Classical Music world. Trained as a violinist, he began his career in the orchestras of Milan, but didn’t remain long. During the late 70’s, at the encouragement of his student Franco Battiato, he delved into the world of the avant-garde. Over the following decades, Pio and Battiato formed a close collaborative relationship – chasing each other across genre and time. As Battiato reentered the world of Pop music during the early 80’s – emerging as an unlikely star, Pio was behind many of his hits, sometimes flirting with equal fame. Perhaps the greatest tragedy of their most productive years – those in the spotlight, was the obscuring and loss of their most important works – the albums which first grew from the joining of their minds. As Battiato’s remarkable catalog on Ricordi and Bla Bla drifted from view, so too did Pio’s Motore Immobile.

While a towering artifact from Italy’s astounding Minimalist movement, and among the first great collaborations between Pio and Battiato, in hindsight, Motore Immobile is a symbolic death knell – a signalling of the end. It appeared at the end of a string of Minimalist masterpieces by Battiato (Clic, M.elle Le “Gladiator, Franco Battiato, Juke Box, L’Egitto Prima Delle Sabbie), and is among the last explicitly avant-garde efforts on which either would work. Change was in the wind, pushing the past from view. For decades, its obscurity has remained a haunting tragedy among fans – needling consciences – echoing from the depths – longing to be heard. While careers rose and fell, hiding in the shadows was one of the most striking and singular masterworks of Minimalism ever composed.

Motore Immobile is an exercise in elegant restraint – note and resonance held to their most implicit need. Ringing with subtly and depth – everything between root and embellishment stripped away. A sublime organ drone, penetrated by deceptively simple structural complexity – quiet interventions of Piano, Violin, and Voice. A sonic sculpture reaching heights which few have touched. A thing of beauty – as perfect as they come – singular, but not alone.

The reemergence of Motore Immobile sits within an important reappraisal of a large, neglected body of efforts made by the Italian avant-garde during the second half of the 1970’s and the 80’s. This incredibly diverse movement, though among the most important of its century, was rarely heard beyond that country’s borders, and only acknowledged by a few within. Of its most striking results, Motore Immobile is among the most important to have remained hidden from view. It now joins its rightful place – resonating within a collective world of shimmering sound, one familiar to fans of Battiato, Lino Capra Vaccina, Luciano Cilio, Roberto Cacciapaglia, Francesco Messina and Raul Lovisoni. Its reissue heralds what is unquestionably one of the most important moments of the year. Emerging for the first time on vinyl since its original pressing, it’s a day for sighs of relief (not the least of which is my own). I can’t thank Soave enough for finally bringing it back, and asking me to play a small role.

Despite all my joy, a sad note hangs in the air. One of the great byproducts of the current landscape of vinyl reissues, is the long overdue attention gained by remarkable and neglected artists. It’s something I was very excited to see offered to Giusto Pio. Few deserve it more. Sadly, just under a week ago – on February 12th, the composer passed away at the age of 91. He had a good run, but fate has robbed him of the ability to witness the celebration of his lost masterpiece. May he live on in its depths. May his name reach the heights that it should. You can check it out below, and pick it up from SoundOhm. I can’t recommend it enough.

-Bradford Bailey

thanku for your efforts and contribution to make this re-issue happen. RIP gusto

LikeLike

giusto pio’s minimal masterpiece was the fuel for my ideas about lowercase… and you also listen to kikyu? very happy to meet you!!!!

LikeLike

Hey Steve! The pleasure is all mine. Is this a remarkable coincidence, or where you tipped to the fact that I wrote the text on A Thousand Breathing Forms that went went up yesterday on SoundOhm? http://www.soundohm.com/product/a-thousand-breathing-forms-6cd-box/pid/29384/

LikeLike