Peter Walker during the 1970’s

During the late 1950’s and early 60’s, McCarthyism still loomed large in America. Despite ending in 1954, like so many of history’s sinister Right-Wing initiatives – with the disgrace of its instigator, and exposure of his corruption, the fear of Communism still permitted the cultural landscape. Folk Music was one of its most notable victims. During this period it was only beginning to creep from beneath the shroud of the Black List, stilled viewed with suspension, and as a threat to the so called American way of life. Efforts were made to keep it from view. These were the sounds of the radical Left – tied to the labor movement of the 30’s and 40’s, and soon to become the soundtrack for social revolution and civil right. They were dangerous and subversive. Within this landscape grew new singular ways of approaching the guitar – the vehicle for its sound.

This is the second installment in my series The Unaccompanied Guitar (Soli, Raga, and Beyond) – dedicated to the canon of guitar music which grew from the innovations, and new approaches instigated by John Fahey during the late 50’s and early 60’s. If you haven’t read this article’s predecessor, I recommend doing so before progressing further. It sets the stage.

Historically, the guitar was most often approached as a rhythm instrument, or used to accompany the voice – particularity in folk traditions. John Fahey was among the first to offer it distinction as solo unaccompanied instrument. His music was referred to as Guitar Soli, or American Primitive and is usually understood as fingerstyle (finger-picked) guitar playing, not accompanied by a voice – practiced by a solo player, but sometimes extending to duos. This description slightly fails as a definition. It offers little distinction from other instrumental guitar music, and doesn’t account for the fact that many of the guitarists that drew on Fahey’s position did occasionally sing – Robbie Basho, being the most notable, and include percussion and other instrumentation, as in the cases of as Sandy Bull and Peter Walker, all three of whom are covered in this installment. The term which is most often applied – unaccompanied, is of almost no technical use. The paradigm of guitar playing which Fahey began, is not defined by the use of the guitar as a solo instrument, or a single stylistic approach. Fahey activated the instrument as a one man orchestra.

The members of Fahey’s own generation, those who followed closely on his heals, are among the most diverse, and difficult to categorize. Most were as singular, innovative, and accomplished as Fahey himself. Unlike a slightly later generation of players, few sound anything like him. One of the complicated things about this generation, was the era itself. It’s hard to know how aware of each other they were in the early years of their innovations. Folk music was still the voice of the underground, and remained largely hidden from view. It’s possible that these unique voices, developed their styles without being aware of, or paying Fahey much mind. That said, they make up the loose canon of guitar music which followed closely on his heals, and represent its remarkable second wave.

For the most part, these artists found themselves housed on two labels, and in a couple of cases shifted between the two. The first of these was Vanguard Records, which at the time was at the center of the Folk movement. It released the records of Sandy Bull, Peter Walker, George Stavis, Robbie Basho, and Fahey himself. The second was Fahey’s own label Takoma, which also issued his albums, and those of Robbie Basho, Leo Kottke, Fred Gerlach, and Peter Lang. For the sake of efficiency and ease, while trying to be as thorough and inclusive as possible, I have limited this selection to these two labels, but it should be noted that there were a number of other players who were working at the same time on smaller and lesser known imprints. These will be covered in the next installment, which begins to deal with more obscure and private press releases. It should also be noted, that I am selecting one album by the following artists. They are simply my favorites – though often chosen with a great deal of inner conflict, particularly in the cases of Robbie Basho, Sandy Bull, and Peter Walker. I am dedicated to the entire catalog of recordings by these three, and can not overstate my hopes that those readers unaware of them, will not end their interest with what I describe.

Sandy Bull – Fantasias for Guitar and Banjo (1963)

I come from a family where the folk music of the 1960’s holds a particular sway. These sounds offered a perpetual soundtrack to my youth. Silence was rare. For that reason – as angry teenagers do, it was a genre I reacted strongly against when I began to develop my own tastes. It was beyond me, to draw the connections I now do – to see it as the original iteration of punk. A music of left-wing social and political rebellion. While the stigmas and barriers of my thoughts began to break much earlier, it wasn’t until the late 90’s and early 2000’s that I began to explore this music at any depth.

Folk music, which I now hold a profound love for – not to mention an extensive collection of LPs, has long been embedded with a sense of personal tragedy and loss. It was the music my mother, with whom I was extremely close, was deeply passionate about. It was her enthusiasm – her belief in the possibilities it carried, which implanted so much of what I continue to chase and pursue intellectually, creatively, politically, and within the art that I love. While we listened to a lot of music together, and I had begun to turn her onto jazz, at the time of her sudden death in 1999 – only reaching the age of 48, our conversations largely centered around our deep devotion to the written word – placing the books we adored into each other’s hands. Most of the music I listened to at that time, was too much for her ears.

Something which shouldn’t go unobserved, is the fact that the image of the 1960’s and 70’s folk scene, as members of my mother’s generation saw and interacted with it, was very different than the one we now hold. I was part of generation which excavated the record bins – pulling and elevating lost gems from the depths. While the history we constructed through this process was more fair and democratic – free from the clutches of capitalism and the recording industry, it is guilty of inadvertently presenting a narrative which does not accurately represent what most people experienced during that time. Names like Joan Baez, Judy Collins, Tim Hardin, Tom Rush, and Phil Ochs, all of whom defined that era, are almost never spoken of, while artists who lingered in the shadows, have now taken their place.

As my early explorations of folk music progressed, I encountered some of the most remarkable music I have ever heard – Nick Drake, Simon Finn, Karen Dalton, Bridget St John, Michael Hurley, Vashti Bunyan, Jackson C. Frank, Sibylle Baier, Anne Briggs, Shirley Collins, Linda Perhacs, Davy Graham, the list goes on and on, music which I knew my mother would have loved, but, in all likelihood, had never heard. Of all that music – the remarkable things I came across, against the years which have passed, I can still feel the clawing need to call her – the sinking of my heart, to think that her life never encountered the wonders of Sandy Bull.

And there is not better place to start, when speak of Sandy Bull, than tragedy. The junkie prince. The self destructive genius. One of the greatest innovators that the guitar has ever seen. Of anyone featured here, it is perhaps most unfair to place him in the shadow of the innovations of John Fahey. With the pioneer of the American primitive style and Davy Graham, perhaps no one has had greater effect on how the acoustic guitar is approached – following a singular path, with countless players pursuing his wake.

We tend to pay attention to the firsts, but the true character of innovation in a moment, is often lost. Sandy Bull‘s Fantasias for Guitar and Banjo, which was released by Vanguard in 1963, is no better case. It emerged during the year following Bob Dylan’s recording debut – the album which, for many, changed it all. When placed side by side, Fantasias makes Dylan’s radicalism feel like that of child. In an era of remarkable invitation and change – where a single year might herald a dozen paradigm shifts, it was easily five years ahead of its time. Nothing like it had ever been heard.

Sandy Bull was an early staple in the Greenwich Village scene, entering it, already addicted to heroin, during his teens. His life and career opens a window into the character of that moment – of those who were there, almost made it, but were rarely heard – lingering in the shadows, drowned out by more famous peers. Part of a trio of friends which was comprised of himself, Karen Dalton, and Peter Walker, within today’s vision of the past, he was among the best of the best – the radicalism and beauty of his music, bleating though the years, still feeling as fresh and relevant as the day it was made.

Bull is an American mirror for the activates of the similarly addiction hobbled and self-sabotaging English guitarist Davy Graham. Both are equally responsible for recognizing their instrument’s links to older and more ancient traditions – beginning their studies of North African Islamic and Indian Classical musics, working at roughly the same time. Bull is the beginning of what became know as Raga Guitar – blending Eastern modes, with the sounds of the West.

It’s hard to know, this many years removed, how many people actually heard Bulls efforts at the time. He has long been cited and referenced by other musicians, but it seems that his fan base within the general public was slim at best. Whatever it may have been, it was far less than he deserved – I’m sure, no thanks to the unreliable and erratic behavior his dependency on drugs provoked. By the time he cleaned up in the mid 70’s, most of the opportunities had passed. Remarkably, and against the odds, he did manage to record four incredible albums at the height of his powers – Fantasias For Guitar And Banjo (1963), Inventions (1965), E Pluribus Unum (1969), and Demolition Derby (1972), each as radical and innovative – ever pushing forward, as the next. There are also two releases of live recordings, issued in recent years, from this period, that are more than worth the time – Still Valentine’s Day 1969 and Sandy Bull & The Rhythm Ace – Live 1976.

Like most artist this close to my heart, I struggle to pick a favorite – doing so begrudgingly. That said, Fantasias For Guitar And Banjo is unquestionably one of my favorite records of all time. Stunning on every count for its guitar playing, it also notably includes contributions by the legendary Billy Higgins, who, during this period, was one of the most sought after drummers in jazz. In my view, this is one of the greatest guitar records of all time – astoundingly ahead of its time – a masterpiece of artistry. I leave you with Blend, which spans the entirety of its first side, but I hope any coming explorations won’t end there.

Sandy Bull – Blend (from Fantasias for Guitar and Banjo) (1963)

Peter Walker – Rainy Day Raga (1967)

The debut album of Peter Walker – Rainy Day Raga, in recent years, has been elevated to a legendary scale – at times out-stepping the respect offered to the output of his dear friend Sandy Bull. A far cry from the neglect it suffered when it first appeared. Walker is was among the most talented and innovative guitarists of his generation – spending considerable time in North Africa, India, and Spain, studying and incorporating aspects of those traditions into his approach. Rainy Day Raga, which was released in 1967, appears at in interesting juncture in the approach to the acoustic guitar – the emergence of explicit reference to Indian Classical music – also seeing John Fahey’s A Raga Called Pat appear on Days Have Gone By and Max Ochs’ Raga on the Contemporary Guitar compilation issued by Takoma, that same year. Robbie Basho had also begun to explore this territory, but wouldn’t title a work as a raga until the early 70’s. Walker is a fascinating figure – often more interested in the music of others, than that of his own – almost a scholar and song collector, over a guitarist. Or perhaps a guitarist so dedicated to the instruments, that he was driven to understand it – its possibilities, potential, and history, far more than anyone else. He recorded two albums for Vanguard during the 60’s, the one before us and 1968’s Second Poem To Karmela” Or Gypsies Are Important, before embarking on years of study of traditions beyond his own.

Rainy Day Raga is stunning on all counts – cited by nearly every contemporary unaccompanied guitarist as a seminal influence. More of an ensemble record than that one dedicated to a solo instrument – including contributions by the legendary flutist Jeremy Steig, Bruce Langhorne, and a number of others, it is unquestionable one of the great guitar records of the 1960’s, belonging here with everything else.

Peter Walker – Rainy Day Raga (1967)

George Stavis – Labyrinths (1969)

If ever there was an indication of my unconventional terms of categorization, and my refusal of orthodoxy, it is the presence of George Stavis’ stunning masterpiece Labyrinths, which, within this list of guitar records, notably does not feature a single guitar. I’ve owned my copy of this album for years, encountering it by chance – one day pulling it from the bins and giving it a spin. I was knocked to knees, unable to believe that I had never heard of the man whose playing so easily took the wind from my lungs. In all those years, I have discovered almost no one, and this includes many serious record collectors, who were aware of it before I brought it to their attention. It is, without question, among the greatest banjo records ever made. Of course the instrument has never captured hearts and minds the way the guitar has, which might account for Stavis’ obscurity, but if ever there was a case for its elevation in our thoughts, it is Labyrinths – his sole LP. Released by Vanguard in 1969, it is a remarkable bridge between jazz – it features an incredible cover of Coltrane’s interpretation of My Favorite Things, the psychedelic era, where folk music had been, and where it was going in the hands of guitarist like Fahey, Basho, Walker, and Bull. It’s essentially a raga banjo record, and as such, unlike anything else you’re likely to have heard. It’s stunning. Every time I pull it out and let the needle drop, it makes my heart race. It rarely makes it back to the shelves for months on end. I seriously can’t recommend this one enough. Find it as fast as you can.

George Stavis – Firelight, from Labyrinths (1969)

Robbie Basho – Song of the Stallion (1971)

In the world of unaccompanied guitar, the adoration surrounding Robbie Basho is almost without parallel. For listeners plumbing these depths, he has long been the first step taken beyond Fahey, and where many stayed. He is as seminal as they come. His playing style so distinct – largely focused on cascading notes played on a 12 string guitar, that it began its own sub-genre within the movement – contemporary players like James Blackshaw and Daniel Bachman deviating and following his path. The pairing of Fahey and Basho represent an unavoidable axis in the history of this movement. So much so, that there is an argument for dedicating an entire piece to the later, as I did the former. Both grew up in Maryland, and were only a year apart in age. They met in 1961 – becoming fast friends. Reputedly, it was Fahey who introduced Basho to the steal string guitar. He rapidly become devoted to his junior’s playing, and with the exception of a handful which appeared on other labels, releasing most of his LPs on Takoma.

Basho is often credited with being the father of the American Raga Style, which, in my view, is not entirely accurate – drawing on the fact that people have historically had more access to his output, allowing him to overshadow the efforts of lesser know peers. While his playing was unquestionably singular, innovative, and ahead of its time, and Indian Classical influences appear early, they are far less notable than those of Sandy Bull, Peter Walker, and at times even Fahey, during the same period. He didn’t begin to explicitly reference ragas until the 70’s, before which his playing has a stronger connection to American folk traditions. Details, semantics, and influences aside, Basho is among the most singular players in the American tradition. From 1965, until his untimely death in 1986 – the result of fluke chiropractic accident, he released a stunning suite of LPs – unlike anything before or since. His playing, sometimes accompanied by own strange brand of singing and spoken word, marked by a quest for higher meaning, charted unknown realms and new potentialities of his instrument.

While it is far from where most fans would suggest new listeners begin, my favorite Basho record has long been 1971’s Song Of The Stallion. Certainly among the less heralded LPs in his output, it marks the beginning of Basho presentation of his own raga style. While the distinction from his earlier playing is subtle, it is more constrained, model, sparse, and arguably emotional. Where ever you begin, for anyone entering the world of unaccompanied guitar, Basho is as essential as they come.

Robbie Basho – A North American Raga, from Song of the Stallion (1971)

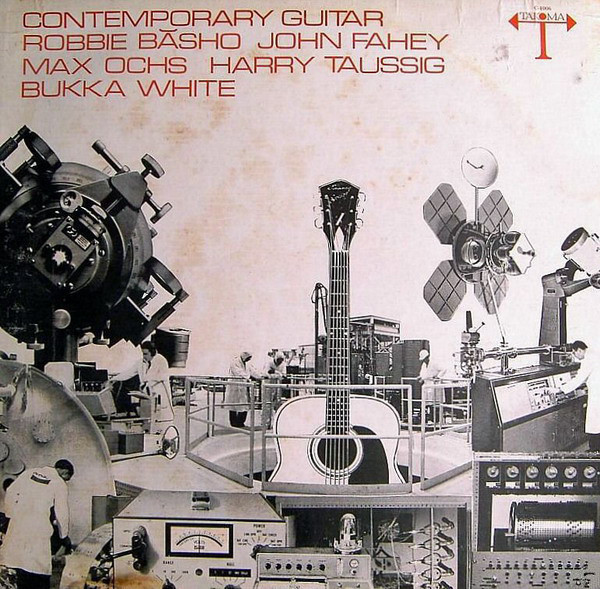

Robbie Basho, John Fahey, Max Ochs, Harry Taussig, Bukka White – Contemporary Guitar (1967)

The Contemporary Guitar compilation – issued by John Fahey’s Takoma Records in 1967, is of deep historical importance – the first recorded collection of unaccompanied guitarists – an image and gelling of the scene. Though musically brilliant, and highly recommended to anyone interested in this area of guitar playing, I considered skipping it – changing my mind for for two reasons. Its historical importance shouldn’t be missed, and from a practical point of view, it offers a perfect entry point into this world – a number of approaches and players in a single hit. Beyond that, I share it for one of its players – Max Ochs, among the most distinct and important guitarists of his generation, who had no other recordings released during this era. While Bukka White was an incredible artist, responsible for a deep influence on the players how followed him – those who make up this canon of music, he was typically an artist who used the instrument to accompany his voice. Fahey and Basho have been covered, and Harry Taussig released an album – Fate Is Only Once, in 1965, which I plan on covering in the next installment of this series.

Max Ochs, like Fahey and Basho, hailed from Maryland. Though a heavily referenced player of the era, tragically, with the exception of the one LP of his band Seventh Sons – Raga (4 A.M. At Frank’s), which is highly recommended, the only recordings to be released during this era appeared on Contemporary Guitar. I’ve been confounded by this fact for years. His contributions have always been among my favorites, and he has, as far as I can tell, been working consistently since – to the present day. Perhaps, caught in the spirit of the 60’s, he just wasn’t interested – preferring to keep his music live. Fortunately, Tompkins square has issued further recordings in recent years – filling in some of the gaps.

Max Ochs is the cousin of Phil Ochs, one of the most famous and noted voices of the 1960’s folk scene. As luck would have it, he appears Contemporary Guitar twice, with a pair of ragas for guitar. His playing is distinct, raw, and marked by a deep sensitivity – leaving the ear desperately wanting more. Sadly, I can’t find a clip of either, so I’ll leave it to you to track down the LP – offering a recent clip of Ochs as temporary substitute.

Max Ochs – Oncones

Leo Kottke – 6 and 12 String Guitar (1969)

Of all the players of the first generation of unaccompanied guitar, Leo Kottke is by far the most most famous and successful – easily crossing into the mainstream shortly after he emerged. He is also my least favorite. While I own and like his first LP – 6 And 12 String Guitar, issued by Takoma in 1969, it’s never gotten much play. I include him because he had an important role in the history and development of this music, and it would be unjust to do otherwise – rather than a deep affection for his work. Fahey discovered Kottke, and held him in great esteem, but younger player’s ambitions quickly out-stepped what his tiny imprint could offer, leaving 6 And 12 String Guitar as his only effort to emerge there. He should have stayed. The context did him good. In my view, it is easily his best LP.

Kottke, during this era, was the unchallenged prodigy of the unaccompanied guitar. His skill and technique threw everyone for a loop, including Fahey, who often mentioned how his junior left him compelled to play faster and faster, pushing him out his depth. Where Basho opened up new possibilities in the approach, so too did Kottke, but, in his case, into the dangerous seductions of technique – historically the greatest pitfall of their instrument. No one denies the importance of skill. Finger picked guitar, elevated to heights of a one man orchestra, is no easy task. But, while nearly every guitarist who came to note was an incredibly proficient player, technique was almost always a means to an end. Fahey was often a slow and sloppy player, but the depth of the emotion and intellect he translated was profound. It was never about be good, just good enough to let the instrument sing and speak. In Fahey’s hands, each note its own creative universe, offering astounding meaning. In this view, Kottke never came close.

Rather than taking his cue from the Blues guitarists, who had set the terms and bar for Fahey and others, Kottke had a stronger connection to Country and Western artists – with their rapid, meticulous approach. His playing is more about the artist, than the music – drawing attention to ones self through technique and skill. Some of this is a matter of taste – what my heart and ear hunt for. I hope my views won’t color 6 And 12 String Guitar too much, and that can be beard with fresh ears. It is an unquestionable axis in the history of this music, and it does have its virtues. There are risks taken and merit – Kottke’s playing yet to be fully battened down. In my view, the album is more of an endpoint than a beginning – to be bought and explored as a counterpoint – for those who are nearing the end of the road, having discovered and exhausted nearly everything else, but for some it may be a perfect place to begin.

Leo Kottke – Watermelon, from 6 And 12 String Guitar (1969)

Peter Lang – The Thing At The Nursery Room Window (1973)

Peter Lang, like most of the guitarists who emerged in the cradle of Takoma Records, was discovered by Fahey. I own his first two records, of which The Thing At The Nursery Room Window is the first. I dig them both. Lang clearly held a great deal of respect in Fahey’s eyes – offering him one of three slots on the second Takoma guitar compilation – the other two being taken by Kottke, and Fahey himself. His only LP on the label, like Fred Gerlach’s Songs My Mother Never Sang, it’s grossly overlooked in the canon of unaccompanied guitar records – a conspicuous victim of the the way histories or currently reconstructed. Gerlach, who was a stunning player, and at the center of the movement, has fallen into the shadow of far more marginal and obscure players – a probably consequence of the fetish for private press folk LPs. Of course, from a collectors point of view, this isn’t entirely bad. This record, like Gerlach’s, still lingers in the bargain and dollar bins. It’s a steal at any price. Lang’s playing strikes an interesting balance between Fahey and Kottke. Like Kottke, his technique is cleaner and more meticulous than Fahey’s, but he pursues this clarity without sacrificing emotional depth and creative intrigue. A beautiful and highly recommend record on every count. In my view, an essential entry, and unjustly neglected artifact, in the canon of unaccompanied guitar.

-Bradford Bailey

Peter Lang – Future Shot at the Rainbow, from The Thing At The Nursery Room Window (1973)

3 thoughts on “the unaccompanied guitar (soli, raga, and beyond), part two – the second wave, sandy bull, peter walker, george stavis, robbie basho, leo kottke, fred gerlach, max ochs, and peter lang ( the takoma and vanguard schools)”