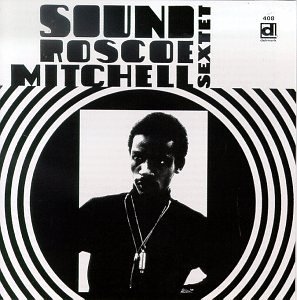

Many years ago, when first I encounter Chicago’s Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) and was working through the catalog of their early gestures, I found myself reading the back of Anthony Braxton’s Three Compositions Of New Jazz. The album was the forth in a serious of recordings by members of the collective, proceeded by Roscoe Mitchell’s – Sound, Joseph Jarman’s – Song For, and Muhal Richard Abrams’ – Levels And Degrees Of Light. Buried in its exploratory text, was the mention of a young tenor saxophonist, Maurice McIntyre, who Braxton believed to be the most important since John Coltrane.

My curiosity was lit. How could a such player have escaped my awareness? As I started to scratch at the annals of history, from which McIntyre was largely excluded, I discovered that he was among the earliest members of the AACM, had played in the ensembles which recorded Mitchell’s Sound, and Abrams’ Levels And Degrees Of Light, before adding his own contribution to the AACM legacy with 1969’s Humility In The Light Of Creator. At the time I learned of it, Humility was all but forgotten. It was a rare record, and in the era before the internet, was almost impossible to hear. It remained a point of curiosity for years. Eventually my digging prevailed, and I located a copy of my own. As I let the needle drop for the first time, a deep force blew from my speakers. Braxton’s praise was well founded. McIntyre was a player of profound depth and talent. How could history have done him so wrong?

McIntyre grew up on the South-Side of Chicago, and from a young age was in and out of trouble. He was an early convert to the world of narcotics, and at the age of 24 found himself serving a two year drug sentence. By accounts, he spent the bulk of his days in prison studying and practicing the saxophone. When released, time had served him well. He was filled with musical fire. Somewhere during the early 60’s he connected with (Muhal) Richard Abrams and joined his Experimental Band. It was this group that eventually birthed the AACM in 1965.

Humility In The Light Of Creator is a remarkable debut. I’m still confounded by its enduring neglect. Its ensemble features Leo Smith, Malachi Favors, Amina Claudine Myers, John Stubblefield, among a number of others. It stands slightly apart from other contemporary gestures of his peers, which might explain some of its neglect, but far from excuses it. It stretches toward a sonic territory which is generally associated with Spiritual-Jazz, rather than embracing the more stark analytical approach of the early AACM. It reaches from the groundwork laid by Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders, and occupies a space all its own. Its tones bleed through time and across cultures. It howls, moans and grooves, but never panders. It’s an unbelievable achievement. I can’t praise it enough.

In the early 70’s McIntyre’s productivity seems to have flagged. Many of the prominent members of the AACM moved to Europe at the end of the 60’s, and remained there for a number of years. I’m not sure why, but McIntyre stayed behind. Separation from his peers, and the creativity they inspired, might account for the period’s slim contribution to his discography, but it’s hard to know for sure. In 1972 he released Forces And Feelings, which is arguably my favorite of his albums. It bridges the gap between the territory demarcated by Humility In The Light Of Creator, and the complex gestures that define much of the AACM. We find McIntyre pushing into unimaginable places, and bringing clarity to his unique creative voice. He skirts closer to outright Free-Jazz with incredibly complex tonal relationships and rhythmic partnerships, but never loses the depth of emotion which characterizes his playing. It ranges from restrained intricate gestures, to a full blown onslaught. The album also features a number of vocal elements by the singer Rita Omolokun, who I am otherwise unaware of. She doubles and triples the album’s already complex tonal landscape and brings it toward towering greatness.

During the early and mid-70’s most of the expatriated members of the AACM began to drift back from Europe. Rather than return to Chicago, many decided to lay roots in New York. This provoked a number of their Midwest counterparts to join them on the east coast, including Muhal Richard Abrams and Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre. 1970’s Free-Jazz (particularly the New York loft era) is a difficult period to chart. It’s grossly neglected. Because very few texts address it, in order to gain any sense for its context, you’re forced to stitch together anecdotes from interviews of participants. Even then, information is thin. Because audiences had largely abandoned the music, many recording opportunities dried up. The presence of records ceases to be an accurate appraisal of a musician’s productivity. To my awareness McIntyre only contributed to one recording immediately following his arrival in New York – Leroy Jenkins’ remarkable outing as leader of The Jazz Composer’s Orchestra from 1975. He also taught for a period at Karl Berger’s Creative Music Studio in Woodstock NY, but beyond this, given his absence from history, it’s hard to know how active he was.

A number of years ago, while I was scouring the internet for information about McIntyre, I came across a message board which touched upon his music. Somewhere within the thread, a woman began to write. She had been McIntyre’s wife during the 70’s. I’m not sure what provoked her to speak out. She seemed unaware of the public nature of the forum, and as though she was reaching out for people that might be able to get in touch with him. She began to stitch together a loose image of McIntyre’s life during the era. It was smothered under a blanket of drugs. Among other tales, she told of his riding the subway with the master tapes from a recording session, nodding out, and losing them forever – a tragedy that we all must now suffer.

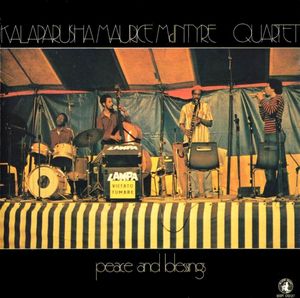

Things start to pick up again during 1977. I’m not sure if he cleaned up, got a handle on it, or more things just started to come his way. There are indications that he was reasonably active through the entire decade, but simply didn’t have the opportunity to record. The tide changed with his contribution of the opening track to the first of the iconic Wildflowers compilations. Between 1977 and 1984 he recorded seven full length records. Four find him as the bandleader. On two he shared the billing (Jerome Cooper, Frank Lowe / Roland Alexander). On the final he’s a member of a collective (Ethnic Heritage Ensemble). It was a very productive time. Many of those records rank among the best of the era.

After 1984 Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre disappeared. He was silent for nearly fifteen years. That they correspond with the height of a drug epidemic ravaging urban America seems far from coincidental. For a time, one the towering talents of Free-Jazz was lost. Beginning in 1998 new recordings started to emerge at regular intervals. Sadly, none reach his former heights. A glimmer remained, but the fire and deep spirit that had raged within him, appears to have been muted by years of neglect and narcotic haze.

One morning in 2010, I was living in London and reading the online edition of The Guardian. I noticed a post for a short documentary film they had produced. Its subject was a Jazz musician down on his luck. I didn’t have much to do, and absentmindedly pushed play. As the short started, a wonky strained saxophone line began. My eyes snapped into focus. I recognized the tune. Though a shadow of its former self, the melody was from the title track from Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre’s Humility In The Light Of Creator. Before me on the screen was a shadow of the once great man. I couldn’t believe my eyes or ears. Someone had found my great mystery and drawn him into the light.

The film is a depressing journey, which verges on being manipulative. It was clearly made to sculpt a “story”, and not by someone with an understanding of, or concern for, Jazz and its history. Its bittersweet. At its conclusion, I was frustrated enough to flirt with writing to The Guardian with my complaints. When I began The Hum, one of the first things I considered was an antidote to its flaws. I understand why the film makers made the film they did. It wasn’t for fans of Jazz, it was a story for those who weren’t. The narrative displays a junkie musician, who once had a shot at playing with Miles Davis, but now works for spare change in the subway, trying to pull a band together for a new record. It brings us into his bleak world of the Bronx projects, introduces us to his equally strung out partner (who is very sweet, and protective of him), and briefly watches him nod out on a park bench. The McIntyre we encounter is an old broken man, barely able to play his instrument.

My frustration with the film flows from many sources. Because its makers didn’t know what questions to ask, and were unaware of the significance of the man, or the remarkable history that he was part of, they lost a rare opportunity. There’s a big difference between someone who had a shot at playing with Miles Davis (but failed to land the gig), and a man who helped build one of history’s most advanced gestures of collective Afrocentric musical intellectualism, and who was thought to be the most important tenor since Coltrane. By default, the film contributes to a larger narrative, downplaying the importance of certain musical legacies for others. The complexity becomes more apparent when addressing the racial divide in America. African Americans rarely have access to media outlets, or the mechanisms that sculpt “orthodox” histories. Their narrative is rarely first person, often authored for and by nonparticipants. The film also takes as a given, the systemic neglect suffered by urban America. It accepts the context of drugs and poverty, without challenge – using it as a Dickensian backdrop for emotional gain. It never asks, how the fuck did we let this happen? How could such a remarkably talented man have been so neglected, and allowed to fall so far? Perhaps more pointedly, how could anyone be?

I wish I had the answers. That I had more tales to tell and could begin to right the wrongs. In 2012, I began returning to New York for extended periods. One of my first efforts was to scour the subways for Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre. I spent hours straining my ears in Union Square and other likely locations. I was determined to find him, to buy him dinner, and to try to hear his story. If nothing else, I hoped to drop the contents of my wallet into his basket. A small gesture of thanks for all the joy his music had brought into my life. My timing must have been bad. I never heard the call of that elastic bound horn. I never found the man who’s music I adore. In November 2013 Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre passed away. Surprisingly generous obituaries ran in a number of major papers, mourning the loss. It does seem The Guardian’s film did some good.

In the end, like most of his generation, and history itself, we are left with fading memories and a few remarkable documents which represent the towering heights of human achievement. Time is laced with singular documents – the one great novel, or album. Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre made more than a few. He was one of his generations greatest talents. A player of profound depth whose accomplishments should be brought from the shadows to live in the light. A flawed man, who suffered at his own hand, and a victim of larger cultural neglect. I encourage you to seek out his sounds and let them ring across time.

Other notable recordings by (or featuring) Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre (not pictured above):