Month: May 2016

on tholl / fogel / hoff’s conditional tension

on 75 dollar bill’s wood/metal/plastic/pattern/rhythm/rock

a documentary on david s ware from 2000

When David S Ware passed away in 2012, the world of Free-Jazz suffered a massive blow. He was one of the forms true champions and brightest lights. Ware entered the New York scene at the end of its moment in the spotlight, and at the beginning of it’s most remarkable period of creativity. After his incredible debut in 1971 on Abdul Al-Hannan’s – The Third World, he worked with Milton Marsh, Andrew Cyrille, Cecil Taylor, and William Hooker, as well as in countless live collaborations sprawling across the “Loft Era.” At the end of the decade he ventured out as a leader, and promptly began issuing a string of striking and ambitious releases into an increasingly unsympathetic context. He is one of those rare players, who in the face of great odds, never compromised and never gave up. A few mornings ago, as I tried to pry my eyes open with a cup of coffee, I came across this documentary about him from 2000. At first it didn’t look that great. The production value is pretty low. I figured I’d watch it for a moment as I woke up, before moving on. I can’t put my finger on why, but as it progressed I found myself completely consumed. It encounters Ware with the last realization of his classic quartet, comprised of Matthew Shipp, William Parker and Guillermo E. Brown. I’m a huge fan of Parker and Shipp. I’ll run at nearly anything they touch. It’s a rare treat to hear them speak and recount across the film. Brown I could take or leave. It’s a film where nothing really happens – a window into the musicians’ world. We hear them practice and try to pull it together. We hear stories and short histories. That’s about it. Yet Ware towers as a striking and compelling figure. You can’t take your eyes off him. You can’t help wonder what he’ll say or play next. The film brings one of Free-Jazz’s greatest voices back into our lives, and reminds us how much he’s missed. At the end of the day, who could ask for more?

-Bradford Bailey

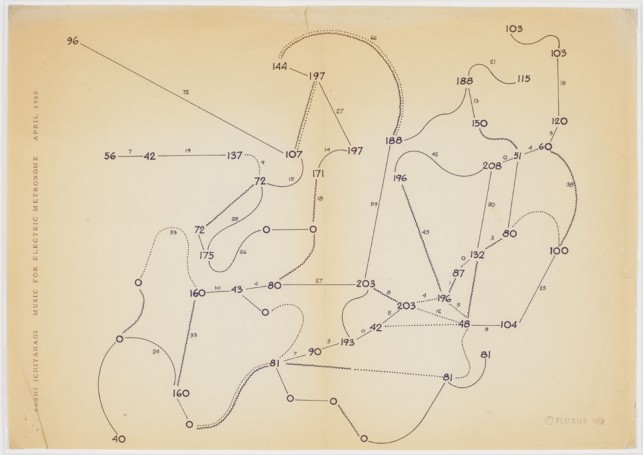

the celestial harp

This Medieval manuscript addresses a theory of how the movement of stars and planets relate to music. It probably extends from the ancient Greek concept of Musica Universalis (Music of the Spheres) which conceived of the relationships between the proportions and movements of celestial bodies as a form of music. These sounds were conceptual, and did not realize themselves to the human ear. The idea is credited to Pythagoras, who believed the celestial spheres were related by the whole-number ratios of pure musical intervals, and thus able to create harmony. It was later expanded by Johannes Kepler in Harmonices Mundi (Harmony of the Worlds) in 1619, which attempts to highlight the presence of God through geometry in the natural world. Though none of this has much application today, it’s nice to encounter beautiful artifacts like this and enter a mode of thought from another time. I hope you enjoy.

-Bradford Bailey

the non-musical works of angus maclise (and ira cohen’s the invasion of thunderbolt pagoda (1968) )

the emergence of jean-jacques birgé and francis gorgé’s avant toute on souffle continu

on black sweat records

codona (don cherry, collin walcott, nana vasconcelos) live in new york, 1984

Codona live in New York, 1984

I’m a huge Don Cherry fan. I own at least 30 of his records, but my relationship with his discography starts to get sticky toward the end of the 70’s. Like many of his peers, he seems to have begun to question his relevance, allowing the influences of popular culture to alter his course. There are notable exceptions, in particular his astounding duo with Ed Blackwell El Corazón from 1982, and Codona, his wonderful collaboration with Collin Walcott and Nana Vasconcelos, which lasted from 1979 until Walcott’s untimely death in a car accident shortly after this film was shot. Codona drew on its three member’s deep engagement with Non-Western musical traditions, spinning them into a brilliant hybrid with their Free-Jazz roots. The resulting sonic tapestry is a dream come true. This film shows the band at top form, snapping into focus the deep tragedy of Walcott’s death, and all that might have been. I hope you enjoy it as much as I do.

-Bradford Bailey