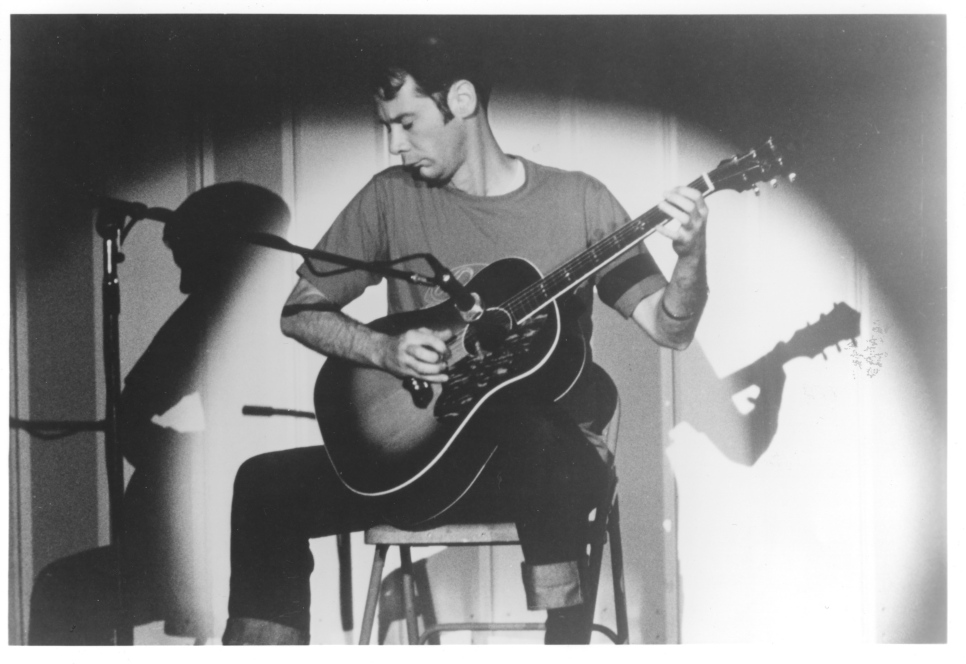

John Fahey, Sometime in the 1960’s

The guitar is everywhere. It’s inescapable. An unchallenged feature of nearly every sonic landscape on the planet. It licks at the heals of teenage dreams, and infects our ears with projections of self-importance, machismo, and limp creative ambitions. It is the aggregator of musical Group-Think. During my mid-teens I developed a strong distaste for this six stringed abomination. It’s ubiquity, with the characteristic lack of ambition of its players, sent me clamoring for music free from its clutches. This simple gesture, and the expectation of music that it provoked, set me on the path where I still remain. Had I known how much time I would spend playing the guitar in my later years (I picked it up in my 20’s), or how many solo-guitar records my collection would come to hold, I’m sure I would have questioned the person I was to become. Despite what came to pass, I’m still sympathetic with this former position. My relationship with the guitar is distinctly love/hate. I loath it’s ubiquity – regularly having to contain my animosity toward its players and their music (five minutes on Pitchfork elevates my blood pressure to dangerous levels), but over the years I came to understand something more. The guitar’s ubiquity is both a curse and a challenge. Those who overcome its familiarity, who chart new territories within its constraints, are far more remarkable for it. This tale doesn’t begin with some epiphany that unfolded in my 20’s (that comes later), but with the sounds of my childhood. It begins with the man who started it all – John Fahey.

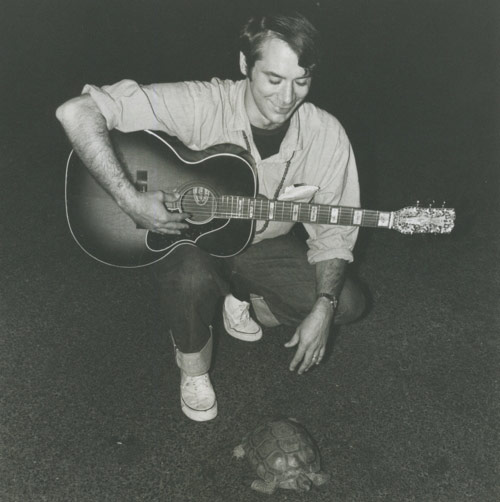

John Fahey, Sometime in the 1970’s

This is the first of a series of articles, exploring the tradition, players, and guitar recordings that grew from Fahey’s efforts during the 1960’s, flourished through the early 80’s, and then found new audiences and practitioners beginning in the late 90’s and early 2000’s. It is a complex music to study, particularly because its easy to be caught by aesthetics, and forget to approach content and intention. Time has offered clarity into the position which Fahey proposed, but it has equally clouded the waters.

John Fahey with Turtle sometime in the 1960’s

Over the course of its history, the guitar was generally approached as a rhythm instrument in ensembles, or as musical device to accompany the voice – particularity in folk traditions. John Fahey was among the first to offer it distinction as solo unaccompanied instrument. The music he created places him as one of the most important, and misunderstood, composers of the 20th century. It falls within an idiom referred to as Guitar Soli, or American Primitive (a term he coined as a tongue and cheek description of his playing), and is usually understood as fingerstyle (finger-picked) guitar playing, not accompanied by a voice – practiced by a solo player, but sometimes extending to duos. Unfortunately this description fails as a definition. It offers little distinction from other instrumental guitar music, and doesn’t account for the fact that many of the guitarists that drew on Fahey’s position did occasionally sing – Robbie Basho being the most notable. It also leaves us wondering why contemporary contributors to the cannon of instrumental guitar music like Davy Graham, Bert Jansch, John Renbourn, among others, fall outside of its ranks. The term which is most often applied – unaccompanied, is of almost no technical use. The paradigm of guitar playing which Fahey began, is not defined by the use of the guitar as a solo instrument, or a single stylistic approach. Fahey activated the instrument as a one man orchestra. This is why, despite singing, Basho falls within the tradition, and the unaccompanied guitar works by figures like Davy Graham, Bert Jansch, and John Renbourn, do not.

John Fahey – Red Pony (1969)

I grew up with John Fahey’s music. Everyone in my family owned his records and played them regularly. My aunt and uncle went as far as walking down the aisle at their wedding to his rendition of A Bicycle Built for Two. His guitar stretches back into my earliest memories. I was lucky. My family generally had great taste in music, and it was rare to find a moment when a record wasn’t spinning on the turntable. Every meal was punctuated by my father, mother, or an aunt or uncle, getting up to make the flip. It would be foolish to ignore the importance this had on the person I became, but I’d be lying if I said I cared about what I heard. Fahey, like everything my family played (much of which I came to love in later years), fell on deaf ears.

Jim O’Rourke – Happy Days (1997)

I found John Fahey for myself when I was 19, living in Chicago. I was in the midst of a love affair with the city’s local music scene – particularity the output of Jim O’Rourke. In 1997 he released Happy Days (on Fahey’s label Revenant). The album rapidly became (and still is) one of the most treasured in my collection – a brilliant work of Minimalism, which can be understood as a sonic distillation of O’Rourke’s working relationship with Tony Conrad and Fahey. It’s one part finger-style guitar, one part drone. Because of my affection for O’Rourke, someone pointed me to the album he had just produced for Fahey – describing it as part of the Happy Days equation. It was called Womblife. My first listen changed everything, and with its counterpart, returned me to the guitar.

John Fahey – Coelacanths (from Womblife) (1997)

There’s no way to sum up John Fahey. There are myths and half truths. There’s a timeline filled with holes. His music is rarely what it seems. The one thing I can say for sure is that he was a genius, and in more than one way.

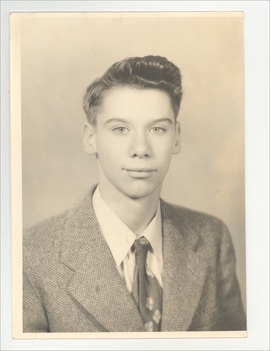

John Fahey as a teenager sometime in the 1950’s

Fahey’s tale begins in the suburbs of Washington D.C (he was raised in Takoma Park). As a teenager he fell in with a small group which included Joe Buzzard and Dick Spottswood. In their company he became immersed in a world music – particularity old Blues, Folk, and Country 78’s, which they pursued with unmatched obsession. Buzzard’s collection of Pre-War American music is now recognized as the most important on the planet. It was from him that Fahey reputedly received his first guitar in trade for a few rare sides.

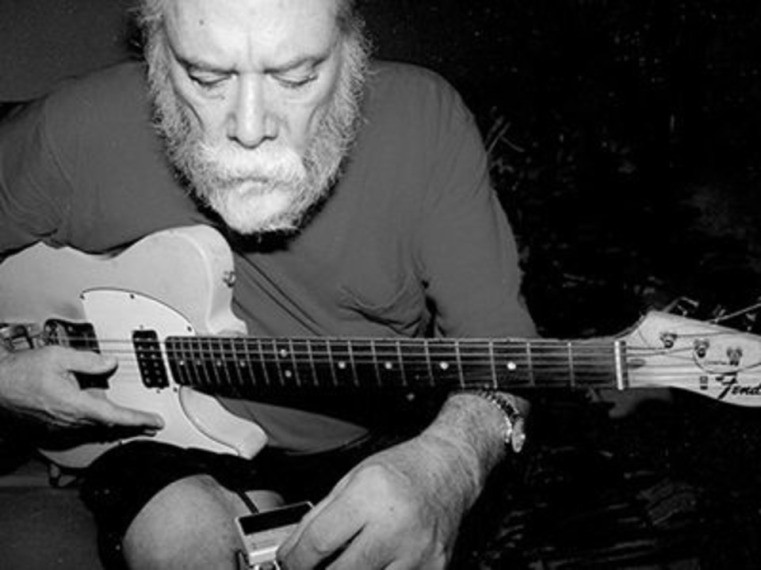

John Fahey sometime in the 1970’s

Fahey’s role in the cultural reappraisal of American folk music, during the 1950’s and 60’s, is wide reaching. Even without his contributions as a musician and composer, he would remain within the annals of history. Setting aside the continued efforts by members of the 1930’s and 40’s radical Left like Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, and Alan Lomax, the Folk Revival began with collectors like Harry Smith, Buzzard, Spottswood, and Fahey, who combed the country for records produced during the recording boom of the 1920’s. Most of these 78’s were all but forgotten – neglected through the Great Depression, their numbers largely destroyed during the Second World War’s shellac drives. Though spurred by a passion for the music they contained, these collectors served as cultural archivists, researchers, and preservationists. Smith, and his American Anthology of Folk Music, which drew from his own collection, is credited as the aggregator of large scale interest in these sounds, but much of what is known of early recorded American music is due to the discoveries of Buzzard, Spottswood, Fahey, and a few others.

Fahey in the late 70’s or early 80’s

It seems that Fahey took to the guitar quickly. His earliest recording (made by Buzzard) date to the late 50’s while he was still a teenager. Though the narrative is hard to untangle, somewhere along the way he tried to teach himself some of the songs on his favorite 78’s. He found it impossible. Things didn’t line up. These players were doing something that defied logic and the ear. As curiosity plagued him, he began to wonder if they were still alive, if he could discover their secrets (it turned out they were using alternate tunings, a practice which Fahey was among the first to adopt, subsequently introducing it to an entire generation of guitarists).

John Fahey – Charley Patton (1970)

After high-school Fahey pursued undergraduate and graduate degrees in anthropology. Not surprisingly, his focus was the music held so close to his heart. He began taking trips through the South to further his research, but by his own account, the true motivation was to find his heroes and learn the secrets of their playing. Through these efforts, he became one of a small number of collectors who began looking for the creators of their favorite 78’s. Few were as successful as Fahey. Among others, he found and reignited the careers of Bukka White and Skip James. His dissertation on Charley Patton has become a standard research tool for anyone studying the Blues.

John Fahey – The Transcendental Waterfall (from Blind Joe Death) (1964)

In 1959 John Fahey founded Takoma Records to issue his first album – Blind Joe Death (placing him as a very early precursor of the DIY movement). Though it encounters an artist at the beginning of his journey, it also finds him fully formed, embracing most of the complex territories that would define his career. Blind Joe Death, like all of Fahey’s subsequent releases, is not what it first seems. It’s impossible to unravel without facing the contexts and conceits within which it was created. The album is effectively a piece of conceptual art. It features two instrumental sides, by two players – Fahey, and the long lost guitarist Blind Joe Death. It is the legend and the legacy, except Blind Joe Death doesn’t exist. He is fiction created and played by Fahey. An attempt to unravel how we understand truth, myth, and history by a contentious anthropologist. Like all of Fahey’s work, there are layers – some easy to spot, others not.

Liner Text from John Fahey’s Blind Joe Death

Most listeners place John Fahey’s music within the American Folk tradition, as part of its revival during the 1950’s and 60’s. It’s easy to see why considering his broad contribution to the field, but this should be immediately dispelled. His work is more appropriately understood within a context defined by composers like Rimsky Korsakov, Stravinsky, Tchaikovsky, Vaughan Williams, Bartok, and Ives – radical works which incorporate elements of folk music. The long standing difficulty in understanding Fahey’s musical proximity draws from the way he ordered meaning. Historically, the compositional practice of incorporating the melodies and structures of folk music into another music, almost never undermines the primary musical context, or the way the components of a piece interact through degrees of importance. Though many composers have attempted it, few challenge the integrity of the dominant form. Fahey’s music is an almost perfect inversion of this. It is an outright attack on how we understand the cultural proximity of sound. He infused the structures and relationships of Classical music (which he had a vast knowledge of) into sounds of Folk and Blues (through instrumentation and delivery), doing so in a way that unraveled the structural integrity of each element. His sounds were interventionary, progressive, and political. Because people define things by what they sound like, rather than what they actually are, Fahey’s project has never been fully understood. His entire body of work is a Trojan-Horse, attempting to reassess the way we build meaning.

John Fahey – Dances of the Inhabitants of the Invisible City of Bladensburg (late 60’s / early 70’s)

Though the distinction can’t be universally offered to all of the guitarists who drew from his position, Fahey should be understood as an avant-garde guitarist and composer. He always bristled at being called a Folk musician, made attempts to correct it, and at times explicate interventions with the way his music was approached. None did much good. Over the course of his career he became an increasingly difficult personality, and more dependent on alcohol to reconcile his frustrations. By today’s standards he was incredibly successful, and widely recognized through the 60’s and 70’s, but by the early 80’s financial trouble forced him to sell his record label – by then housing his most important works, and those of many of other artists. Before the decade was out, he was a drunk, living in his car, surviving by combing thrift stores for rare Classical records – selling them to collectors to provide a meager existence.

John Fahey, Barry Hanson, and Mark Levine’s interviews with Son House

Fahey made complex music, masquerading as one thing, while being another. For it to be fully understood, a listener must be willing and able to approach and understand it. They must face their own preconceptions and failures. The guitarist’s faith in his audience was profound. He believed they were capable of embarking on the journey he proposed, and was let down by their unwillingness to do so. This is where he bears some of the blame. Like all performers, he was dependent on his audience. Despite being a difficult personality, he was not outwardly aggressive. Rather than fighting their desires, he often was guilty of giving them what they wanted to hear – contributing to the very condition that tore him apart.

Jim O’Rourke & John Fahey in 1998

My encounter with Fahey during the 90’s, and my subsequent relationship to his earlier catalog of recordings, was not an accident – nor was his place within the musical scene where I found him. At the time, figures like Jim O’Rourke and Glenn Jones (with his band Cul de Sac) were doing for him what he had done for Bukka White and Skip James decades before. Beyond revitalizing his career, they were attempting to illuminate Fahey’s project for new audiences, correcting the errors of the past.

Fahey in the 1990’s

My generation, with members of the one which proceeded it, represent interesting variants on Fahey’s. Left with the ashes of Punk, like early members of the Folk Revival, we harbored a deep distrust of the commercial media machine, and a profound belief in the democracy of sound. With little to call our own, and an insatiable thirst, we approached recorded music as a form of cultural artifact – a way to understand and connect with history and the world around us. We became amateur anthropologists. Decades were spent scouring the planet for lost and underappreciated albums, for voices like our own. We intuitively embarked on a reappraisal of history, restructuring it, returning neglected and under appreciated works of art to the world – hoping to offer greater context and insight. Fahey is one of many artists that returned to us through these efforts. It was done without nostalgia – a means for his work to gather greater understanding, and for it to exist as a contemporary operation. Artists like O’Rourke and Jones recognized Fahey as a member of the avant-garde. They gave him shelter in our world, with room to express himself. Because of this, there are effectively two bodies of work within his career. There are the recordings that stretch from 1964 to 1992, and there are those released from 1997 until his death in 2001. The larger cannon is as I have described. A strange remarkable music played on acoustic guitar which appears to one be thing when it is in fact another. The last phase of Fahey’s recording is different – clear and distinct in its proximity as an avant-garde music, and largely played on electric guitar. It is often difficult and abrasive. What’s fascinating is that from a technical point of view, Fahey’s playing hardly changed. There is a new looseness to his attack, and the tempos slow down, but he is still playing fingerstyle built around the same relationships and conceits that are present across his entire career. The only substantial difference is that he was playing on an electrical guitar with an occasional effect or two. It is as though, through his last gestures, Fahey is offering his listeners a final clue – a way to understand his legacy and vast body of work. He is reminding us that music has two operations – the way it sounds and what it is and does.

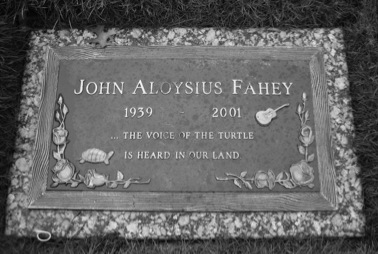

Fahey’s Grave

Despite all the intellect, attempts to deconstruct meaning, and interventions that Fahey’s music possesses, more than anything he was a player of profound depth and emotion. His fingers had unparalleled sensitivity. I have never heard another player bring what he does to the guitar. His catalog is vast, and despite superficial appearances, is incredibly diverse. He never stopped challenging himself, pushing the bounds of composition, or what his instrument was capable of achieving. Not including compilations, and the cases where he recorded multiple realizations of the same album, there are roughly 40 releases spanning the 43 years of his recording career. I have (and love) nearly every one. Offering a concise list of what I would deem as essential albums from Fahey’s discography feels like a fools errand, but this is exactly what I’m attempting to do. This selection draws from those closest to my heart, while trying to access the larger conceits which bridge his entire body of work. For those unfamiliar ears, may they be only the beginning of your explorations of one of America’s most neglected and misunderstood avant-garde composers.

John Fahey – Your Past Comes Back to Haunt you, The Fonotone years [1958 -1965] (2011)

This is one of the most recent, but historically important, entries in Fahey’s catalog. Released in 2011 by Dust to Digital, and guided into existence by Glenn Jones, Your Past Comes Back to Haunt You is a five CD box set of previously unissued recordings made by Joe Buzzard of his friend between 1958 and 1965. Its contents predate or bridge the periods in which his first three releases were recorded, making some the earliest available documents of Fahey’s work. None were made for commercial release, making them incredibly poignant from a historical perspective, and offering a rare insight into his development. They are raw and honest, but should be approached with elevated awareness by listeners. This is not because they are lacking, Fahey was already a striking player by his late teens, but because his conceptual conceits were not fully developed. If approached without an eye on the big picture, they could open the possibility of misreading his already deeply misunderstood legacy. They sometimes elude to what people presume him to be, a member of the folk revival drawing on historical traditions, rather than what he became in a few short years. That in hand, the set is unlike anything else in Fahey’s catalog, sprawling, brilliant, insightful, and historically important – bringing us into the beginnings of Fahey’s project, and allowing greater understanding of how brilliant he was at even at his earliest steps. It also offers a fascinating insight into the origins of the project realized by Blind Joe Death, with a substantial number of early recordings made under the alter ego Blind Thomas. It’s an essential acquisition for anyone interested in Fahey’s larger body of work, and for those seeking to understand where one of the greatest contributions to 20th century guitar playing began. Dust to Digital still has copies, so get it before it goes.

John Fahey – The Portland Cement Factory at Monolith, California (from Your Past Comes Back to Haunt you, The Fonotone years [1958 -1965] )

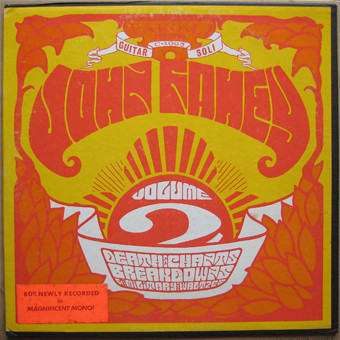

John Fahey – Volume 2 / Death Chants, Breakdowns & Military Waltzes (1963 /1967)

Death Chants, Breakdowns & Military Waltzes is Fahey’s second album. Of all his records it is probably the most well known, and for good reason. It’s incredible. When people think of the archetype of his sound, this is probably what they hear. The leap from Blind Joe Death is striking. It’s compositions begin to stretch toward the complexity that defines Fahey’s releases from later in the decade. His playing and ideas are clearer, more confident, and increasingly singular – marked by the careful slow delivery of notes that distinguishes him from so many of the players who followed him. This is the pool from which all fingerstyle guitar draws, but often fails to understand. Beyond it’s individual brilliance, historical importance, and personal affection, I’ve chosen to include it because it offers a secondary insight into Fahey’s personality and practice. Like many composers of his caliber, he was deeply critical of his own efforts. Death Chants was recorded in 1963, and issued in 1965, but with the albums that sit on either side of it, Fahey found himself increasingly disappointed by the result. In 1967 he rerecorded all three and issued them again. The above image, and the below recording, are from the second issue. This is the album where I recommend everyone begin.

John Fahey – Sunflower River Blues (From Volume 2 / Death Chants, Breakdowns & Military Waltzes) (1963 /1967)

John Fahey – Volume 6 / Days Have Gone By (1967)

Days Have Gone By is the sixth entry in Fahey’s discography, a watershed, and my favorite “volume” in the early phase of his career. It features the beginnings of a remarkable leap in his playing, foreshadowing the next decade of his releases. Though much of the album bears some aesthetic similarity to its predecessors, we find Fahey looser, and more ambitious – straying from the kinds of relationships that could be confused with Folk, and into territories saturated with complex harmonic relationships and dissonances. The most notable departure comes with the two parts of A Raga Called Pat. Keeping in mind that 1967 is also the year Peter Walker’s iconic Rainy Day Raga was issued, the track places Fahey’s use of the term, and explicate incorporation of Indian Classical music, as the first, or close second, of its kind on guitar. Either way, it is unlikely that they two guitarists were aware of the other’s advances while recording. Beyond the new structural approach, A Raga Called Pat also presents the debut of explicitly avant-garde gestures in Fahey’s work. Creeping from the background are processed field recordings of thunder, trains, birds, and environmental sounds. It is a direct intervention with his listeners, offering them access into the meaning of his efforts and their proximity. It’s an album which sends shivers down my spine with every listen. It’s wide open – filled with space and emotion. An absolute must.

John Fahey – A Raga Called Pat – Part One (from Volume 6 / Days Have Gone By) (1967)

John Fahey – A Raga Called Pat – Part Two (from Volume 6 / Days Have Gone By) (1967)

John Fahey – Requia (1967)

Requia is fascinating on a number of levels. It is the first of a pair recordings (with the equally stunning The Yellow Princess) which find Fahey on Vanguard Records, in the company of a community of solo guitarists pushing the bounds of his early propositions – Sandy Bull, Peter Walker, and slightly later Robbie Basho (all of whom feature in the next installment of The Unaccompanied Guitar (Soli, Raga, and Beyond) ). During this period, Vanguard was one of the most renowned Folk Labels – hosting the releases by The Weavers, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Odetta, Joan Baez, Doc Watson, and countless others, making it an strange place for Fahey to debut his most explicitly avant-garde effort to date. Requia was a revelation when I first bought it. This was only a few albums into my explorations the guitarist’s 1960’s catalog. It cracked everything open, revealing that the artist I’d encountered during the 90’s had been at it all along. It begins within fairly familiar territory with three instrumental guitar works – Requiem For John Hurt, Requiem For Russell Blaine Cooper, and When The Catfish Is In Bloom. Though brilliant, they feel more restrained, virtuosic, and folky than what we encountered on Days Have Gone By. It isn’t until the second side that we realize that Fahey has set his listeners up for the fall. Requiem For Molly stretches almost entirely over its length. The work is unlike anything else in Fahey’s catalog. It is an explicate work of Musique Concrète – an aggressively difficult sound collage, which he forces his playing into. I can’t imagine what fans thought when they heard it, but it offers a rare clue into Fahey’s practice. Thought I expect most people consider it an anomaly, a product of 1960’s creative zeitgeist, or of the guitarist’s personal eccentricities, there’s considerably more to it. It’s both a statement of proximity – explicitly aligning himself with the avant-garde, and a key to his practice. All of Fahey’s work addresses the sonic artifact (never forget he was an anthropologist) – how fragments of the past exist in the present, and carry cultural meaning with them. His songs are something akin to a compositional collages – contending with the legacies of the music we are left with. Musique Concrète is a creative intervention with existing sounds. A way of restructuring our relationship to, and the meaning held by, the sonic landscape in which we find ourselves. It’s description and operation are Fahey’s project in a nut shell, making his use of it here a profound insight.

John Fahey – Requiem For Molly – Part One (from Requia) (1967)

John Fahey – Fare Forward Voyagers (Soldier’s Choice) (1973)

Fare Forward Voyagers (Soldier’s Choice) is arguably my favorite Fahey record of all time, but it’s also bittersweet. It falls at the end of an incredible stretch of recording which gave us Days Have Gone By, Requia, The Yellow Princess, The Voice Of The Turtle, and America. It is followed by a period of inactivity, and then a reduced ambition across the guitarist’s subsequent releases (until 1997). It is the last great gesture in the first phase of his career. It is comprised of three long works – When The Fire And The Rose Are One, Thus Krishna On The Battlefield, Fare Forward Voyagers, which work together seamlessly as a totality, representing some of Fahey’s most ambitious compositional efforts, as well as his finest playing. It is stunning – abstract, concise, and completely singular, finding the guitarist out on a limb and within a territory that is entirely of his own making and defying all association. Rather than do it the further injustice of my words, I leave you with the entire album below to listen for yourself.

John Fahey – Fare Forward Voyagers (Soldier’s Choice) (1973)

John Fahey – Railroad I (1983)

Railroad brings us to a complicated place in Fahey’s career. The late 70’s and 80’s saw the guitarist pulling back from his former avant-garde gestures – seemingly resigning himself to the position that his audience wanted to understand him as occupying. Truthfully, Fahey didn’t have a bad moment in nearly a half century of activity, there were just varied degrees of ambition. Railroad I is a diamond in the lows. Easily my favorite album between Fare Forward Voyagers (Soldier’s Choice) and his return during the 90’s. It’s pretty straight forward, largely resting within the territories he explored during early 60’s. Some of the more difficult tonal relationships from the last decade are still present, and his playing is at the top of his game, it just sounds a bit more like a “folk guitarist” than I imagine the composer would have been comfortable with. Definitely a gem, an important insight bridging his more dynamic efforts, but to be approached with caution toward the end of completing your Fahey discography.

John Fahey – Frisco Leaving Birmingham (from Railroad I) (1983)

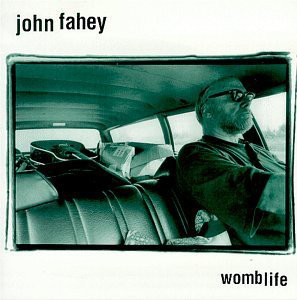

John Fahey – Womblife (1997)

And here we come to Womblife, the Jim O’Rourke production around which the axis of my approach to Fahey was formed. Of all of Fahey’s albums, it is probably the most “difficult”. I know a lot of people who don’t like it, but I love it and owe it a great debt. The record is the beginning of Fahey’s reemergence. The start of a few short years during which he held nothing back and offered greater transparency into the nature of his playing and his proximity within culture. It also represents the greatest departure from the stylistic approach he is most well know for. At times it is so angular and sparse, that it seems closer to Derek Bailey than his former self. What’s interesting is that much of the album finds him returning to the most ambitious gestures within Requai and Days Have Gone By, with his playing being worked into, and responding to, processed sound. It makes you wonder how different history might have been, had his early audiences been more receptive to his earlier presentations of this world. This is easily the most singular and jarring work in his discography, and essential for accessing the themes that stretch across the entirety of his career.

John Fahey – Eels (From Womblife) (1997)

John Fahey – City of Refuge (1997)

Also released in 1997, City of Refuge is the perfect sonic distillation of Fahey’s arching career and projects. Though I love all his late works with equity, this is probably the most elegant and my favorite of the bunch. It is comprised of a 20 minute grinding piece of proceeded abstract sound – drawing some of its samples from the Stereolab, acoustic guitar works, angular electric guitars similar to those found on Womblife, and the use of sound collage and soundscapes as a foil for his playing. It’s the full package, and comes together seamlessly in a way you couldn’t predict before hearing it. An absolute stunning piece of work that is essential in any collection.

John Fahey – On the Death and Disembowelment of the New Age (From City of Refuge) (1997)

John Fahey – Hope Slumbers Eternal (From City of Refuge) (1997)

-Bradford Bailey

Rare and precious. An article i shall turn back to. Soon.

LikeLike

Great article, keep it up. Like you I’d been exposed to Fahey in my youth but didn’t “get it” until much later, thanks to Forced Exposure among others. Only thing I’d add to this is a nod to Byron Coley’s Spin article on Fahey. The effect that it had on Fahey’s ’90s revival that can’t be overestimated, and even Fahey knew it (as evidenced by his on-stage trashing of Byron on at least one occasion)…

LikeLike