It must be said before I begin, this kind of list is bound to fail. They are gestures of taste, and, as every music fan knows, it’s impossible to justice to any form of music, particularly one as sprawling and diverse as free jazz, with a slim number of picks. But they do some good – small illuminations (or reminders) in the dark. Inevitable failure is no reason to not try.

Free jazz towers among my life’s great loves. It has carved a path through my years – the music which, despite the sprawling diversity of my tastes, resonates above all others – filled with fire, rage, politic, intelligence, stunning sensitivity, and range – creative heights and ambitions which few have reached. It is one of the greatest forms of music which has ever come to be. It is a beast. A monster. The voice of Black America planting its being and consciousness in the world. A decidedly African American voice, becoming a music so diverse and sophisticated, with so many distinct cultural iterations, not to mention cross-cultural collaborations – played by men and women from every corner of globe, that it offers an image of utopia in sound. It is the sublime – a glimpse of true, unmediated freedom in our midst. Democracy and music at its best.

I came to free jazz, still in my early teens, during the beginning of the 1990’s – disillusioned, watching the music through which I had found my first sense of belonging, community, and creative resonance – punk, enter the mainstream – too often becoming a clamoring, corporate shill – just another accessory in the mall. I was shoved from my sonic womb – stripped, out in the world, looking for new sounds which spoke to my heart.

Those were different times. It was the beginning of the CD era. People were tossing out their LPs en masse. It wasn’t uncommon to see massive piles of the abandoned and unwanted in the street. Yet, relatively speaking, very little had been reissued on the format taking vinyl’s place. Particularly in the case of avant-garde jazz, a great many seminal albums wouldn’t see CD reissues for another ten years or more – just in time for the beginnings of the medium’s soon to be rapid demise. Obscure music from the past became incredibly hard to find – especially for a young man raised an hour or so north of Boston, lost in the woods.

And so, out on my own, I came to free jazz by accident, following a slightly unlikely path – slowly working my way through John Coltrane’s discography, gathering my allowance, buying one after the other chronologically, month after month. When I arrived at the albums on Impulse, everything changed – the voices and souls of John Tchicai, Marion Brown, Archie Shepp, Pharaoh Sanders, Rashied Ali, Jimmy Garrison, and Alice, came screaming into ears – the seeds for countless revelations to come.

During those years, most musical discoveries came from magazines, zines, the recommendations of friends, and, importantly for lone travelers like myself, by following the threads and crumbs offered on record sleeves. If you liked something, you chased down the other albums on which its players played, or on the label on which it was housed. Over the decades since, I’ve found, like so many others, that my early early discoveries within the canon of avant-garde jazz played a heavy hand in my subsequent tastes. Most free jazz fans, at least those I’ve known, began with Ornette or Cecil – efforts often more brittle, frenetic, and cerebral than those of Ayler and Trane. Thus my ear tends to hunt for something different – rarer and further afield – that big sound, often taking its time – a slower paced energy – a rumble, favoring tension built from the interplay of structure, rhythm, and tone. I veer toward emotiveness, heart, and intricacy, over the archetype of hard blown fire. It’s why late Coltrane, the AACM, Cherry, Tchicai, Shepp, and Sanders will forever form my root. It’s also why this list will look fairly different than most.

For my generation – those raised during the 80s, a decade which paid few favors the contexts of avant-garde jazz, there weren’t many helping hands. No one talked about this music – often not even those who had made it, many, during those years, turning their backs and choosing a tamer path. We were on our own, covered in dust, digging in the bins for history’s waste. There was one notable exception. Appearing in 1996, the year I graduated from high school, within the second issue of Grand Royal Magazine, was a list entitled Top Ten From The Free Jazz Underground – fourteen towering masterpieces of free jazz, complied by Thurston Moore. It was a revelation, offering guiding light. Of all the record lists I’ve ever encountered, comprised of Dave Burrell’s Echo, Milford Graves & Don Pullen’s Nommo, Arthur Doyle’s Alabama Feeling, Sonny Murray’s Sonny’s Time Now, Ric Colbeck’s The Sun Is Coming Up, Rashied Ali & Frank Lowe’s Duo Exchange, John Tchicai And Cadentia Nova Danica’s Afrodisiaca, Peter Brötzmann’s Nipples, The Marzette Watts Ensemble’s The Marzette Watts Ensemble, Marion Brown’s In Sommerhausen, Black Artists Group’s In Paris, Frank Wright’s Uhuru Na Umoja, Seikatsu Kōjyō Iinkai’s Seikatsu Kōjyō Iinkai, and Cecil Taylor’s Indent, Thurston’s is the daddy of them all. It’s a mother fucker. I spent years chasing its contents. That god damn Watts still eludes me now.

While a great deal of its information has come to be taken for granted, it’s worth remarking on what Thurston pointed us toward. Not only did it hint at four of the great treasure troves of free jazz – Freedom, America, MPS, and BYG (you could say five, since Brötzmann’s catalog is the most usual pathway into the wonders of FMP), but, most importantly for myself, it was one of the first wildly published indications of the towering accomplishments housed on private, artist run labels during the 70s and 80s – in this case Graves’ Self-Reliance Project, Charles Tyler’s AK-BA, LeRoi Jones / Amiri Baraka’s Jihad, Rashied Ali’s Survival, and the Black Artist Group’s BAG. He told us where to look, the influence of which runs its way through this list, written 22 years after his own.

I could dedicate a great deal of time waxing lyrical about the wonders of this music – its sounds, philosophies, being, identity, and politics, but, as is the case with all great music, it speaks for itself. It doesn’t need my words, only my finger to point – sharing what I’ve loved and found along the way. For the point of clarity, I have applied certain heavy constraints to my process of selection. If I were assembling a my true free jazz top ten, there would likely be more than a few overlaps with Moore’s selections. Nommo, Alabama Feeling, Duo Exchange, Afrodisiaca, and In Paris remain among my favorite records of all time. With the exceptions of Frank Wright and Frank Lowe, I have done my best to only include artists who where absent from his list. I have also made a point to only include one album from a given imprint, hoping to offer as many crumbs to follow as I can – thus, for example, I could have easily included Charles Tyler’s records on AK-BA, which are extremely close to my heart, but chose, because I adore it and it is less well know, David Wertman’s contribution the imprint’s slim discography, then choosing an equally good album by Tyler on Nessa. In addition to this, I have opted to pass over a great many albums which hold similar rank in my heart, but which are more likely to be well known or independently encountered- those by artist like The Art Ensemble of Chicago, as well as the incredible solo efforts by its members, Muhal Richard Abrams, Anthony Braxton, Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, Eric Dolphy, Archie Shepp, Don Cherry, Pharaoh Sanders, Eddie Gale, Sun Ra, Etc. Like Moore’s, and perhaps even more so, this is a piece about a truly underground, autonomous, and independent music, most often existing beyond the bounds of mainstream support. I have also taken a decidedly more American and Afrocentric, if not at times explicitly Black Nationalist, position, only including albums made by Americans, and only one by a white band leader – David Wertman. This is the result of politic as much as taste.

Free jazz has almost always been a multi-racial, multi-national, and multi-cultural music. The seminal quartet which recorded Ornette Coleman’s The Shape Of Jazz To Come – generally regarded as the first recorded work of free jazz, features a white player – Charlie Haden. The New York Art Quartet included John Tchica, who was Danish, and Roswell Rudd, who was white. Cecil Taylor’s first record features Buell Neidlinger and Steve Lacy, both of whom were white. Albert Ayler’s first recordings are entirely backed by a Swedish ensemble, while Eric Dolphy’s final gestures, recorded in 1964, are backed by different groupings of European players. Even early iterations of the AACM, the great collective effort of black creative music, included white contributors. Almost as soon as the movement had begun, it sparked new forms across the globe, giving way to countless cross-cultural conversations and collaborations, particularly notable between American players and their cousins in the Incus, FMP, ICP, and Japanese camps. Because of the make up of its fan base, facilitators, ensembles, and artists, this music is one of the great historical actors in the fight against racism and cultural division. It is global discourse of many streams. All that said, there is a big difference between being part of, or joining, a conversation (or fight), even when you make it entirely in your image, and beginning it. Free jazz should always be regarded, in its origins, as an African American art form. Just as figures like Ives and Cage, as American as their music was, should be regarded as belonging to a European tradition.

Of course these are the mysterious wonders. It’s worth asking why this music, so decidedly African American in its root, often created with the intention of the African American community being its primary or exclusive audience, has drawn so many diverse artists and fans into its fold. These days, there are strong indications that those bearing free jazz into the future, new and young players and fans alike, only rarely come from the culture from which it sprang. It’s clear that there is resonance which speaks beyond the boundaries of national identity, culture, and race. To my mind, this is part its profound power, but its also important to acknowledge that there are hierarchies of access within. It is a music, at the root, which is first black, then American – with slightly later, culturally specific iterations within other countries, then human. Having been born a New England WASP, I will never fully be able to hear what African Americans do. This is their music – their hearts, minds, history, culture, experiences, and souls. Being American, I hear something which those from other countries will not, as I can not hear what they do within their own indigenous realizations. Yet this music is so powerful, so human and deep, that it speaks to us all, regardless of its point of origin, or our relationship to that point. It is a space of collaboration, where we all may join. That is, as long we acknowledge where it all began and why.

We are all victims of our taste. For whatever reason, particularly in the case of free jazz, my ear has always been drawn toward the African American voice. It may sound shocking and sacrilegious to some, but as much as I love the work of players from every corner of the globe, the voices of younger African Americans, those like Tomeka Reid and Matana Roberts, sing in my ear far more than those of their older, more experienced international counterparts – Peter Brötzmann, Evan Parker, etc. It is what it is – resonance, taste, and who I am. Call it what you will, but it is part of why this list looks the way it does, and thus is worth acknowledging and making as transparent as I can. Whatever I assembled, it would be guilty of a great deal of inevitable bias and neglect.

And so, in the spirit of Thurston Moore, who couldn’t constrain his list to ten – stretching it to fourteen, I do the same – my own Top Ten From The Free Jazz Underground, taking on two more – sixteen towering masterpieces – a sliver among my favorite free jazz albums of all time. May there be a few revelations, or at least reminders, within. May this music, the closest to my heart – among the greatest of all the art forms, sing in your ears.

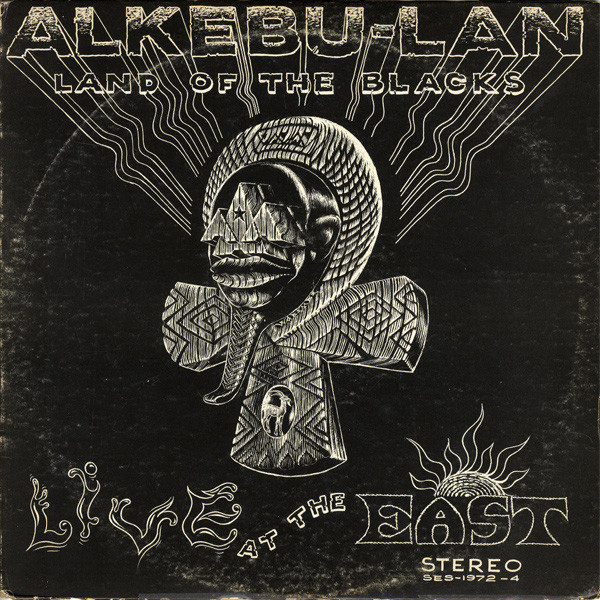

Mtume Umoja Ensemble – Alkebu-Lan – Land Of The Blacks (Live At The East) (1972)

Alkebu-Lan – Land Of The Blacks, made by Mtume Umoja Ensemble – including the famed voices of Leroy Jenkins, Stanley Cowell, Gary Bartz, Andy Bey, Billy Hart, and many others, was released in 1972 by Strata East, rising to become one of the rarest and most sought after object in the label’s famed catalog. It’s a mean motherfucker – an unmediated document of the pure fire and incredible power of Black Nationalist free jazz. It towers among my favorite records of all time – ironic, considering that it’s one which was never intended to be heard by white folks like me. The venue within which it was recorded – Clinton Hill’s famed The East, maintained a strict admittance policy, only allowing people of color to pass the front door. There’s even a story of Miles Davis showing up one night with a group of friends, some of whom were white, and being turned away cold. Black Nationalism was for real. It offered elusive, safe space, and didn’t fuck around. It’s arguably because of the safety and limited inclusion of this enviroment, that Alkebu-Lan – Land Of The Blacks is so god-damn good. It’s filled with justifiable rage, and says what it wants – an album of rare honesty, pride, emotion, expression, and depth.

There’s another historically interesting twist. The Mtume Umoja Ensemble was lead by James Mtume, a percussionist who, during this period, played regularly with with Miles Davis, Buddy Terry, Sonny Rollins, Pharaoh Sanders and others, as well as being the son and nephew of the primary members of the Heath Brothers, with whom he also worked. After recording only two LPs as a band leader – Alkebu-Lan and 1977’s Rebirth Cycle, Mtume left the world of jazz, going on to have a fairly successful career as a modern soul and disco artist, most noted for the track Juicy Fruit, later famously sampled by Notorious B.I.G. (who serendipitously grew up only a few short blocks from The East). Because of the radical shift in his career, I’ve heard rumors that Mtume prefers that his former efforts as a band leader – those featured on Alkebu-Lan and Rebirth Cycle, remain out view, making it tragically unlikely that they will ever see an official reissue.

Made with sprawling ensemble of thirteen players, Alkebu-Lan is a howling storm set forth on the world. There isn’t an ounce of restraint on its four sides. It makes the emotional onslaught of punk and hardcore sound like a childish temper tantrum – a perfect melding of intellect, intricacy, the heights of artistry, politics, and pure rage. Despite all that it unleashes, it feels incredibly considered and composed. Alkebu-Lan is a rare and wonderful thing – a diamond standing outside of its time. Sadly it isn’t easy to track down, subsequently commanding a pretty heavy price tag. That said, it’s worth every minute it takes to find, and every penny spent. Check it out and you’ll know what I mean.

Mtume Umoja Ensemble – Alkebu-Lan – Land Of The Blacks (Live At The East) (1972)

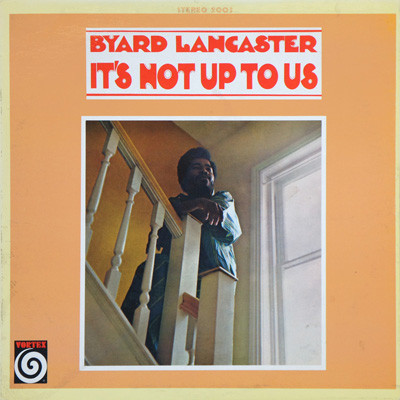

Byard Lancaster – It’s Not Up To Us (1968)

Fuck I love this record! I should just shut up, say listen, and leave it at that. Byard Lancaster was a monster whose name has never entirely received its due. He worked with the best of them – Sun Ra, Bill Dixon, Marzette Watts, Doug Hammond, Khan Jamal, Sunny Murray, Odean Pope, and a great many others, but it was as a bandleader where he truly shined – displaying a remarkable sense of restraint in his own playing, while sculpting a sound which unleashed its power through others. There are few equivalents. Unfortunately, the majority of the efforts which appeared under his name, issued by Palm or his own Dogtown Records, remain incredibly hard to find. That said, It’s Not Up To Us, issued in 1968 by Vortex, is among the easiest to lay your hands on, and definitely among the best.

It’s Not Up To Us is one of those records which unleashes the sort magic which is hard to lay your finger on – something which, at least to my mind, draws heavily on the fact that it is such a focused work of interdependence and collaboration. There are no stars, only a unified body of sound. It’s a mind-meld. Even then, it’s hard to avoid mentioning Sonny Sharrock’s guitar playing. It’s something else, arguably among the best recorded moments of his career, but even those heights would have been unlikely without his interplay with the bassist Jerome Hunter. He’s just one piece in the puzzle – an ensemble which, with the exception of Lancaster on flute and alto sax, is entirely made of rhythm players – Hunter on bass, Sharrock on guitar, Eric Gravatt on drums, and Kenny Speller on percussion. (The interplay between Gravatt and Speller is also particularly stunning)

It’s Not Up To Us is a chugging, soulful, wild, and interlocked monster – a polyrhythmic beast, often so complex and intertwined that it’s hard to distinguish head from tail. A hurricane, offering different vision of what free jazz could be – falling far closer to late Trane, Alice, and Pharaoh, and just about as essential as records come.

Byard Lancaster – John’s Children, from It’s Not Up To Us (1968)

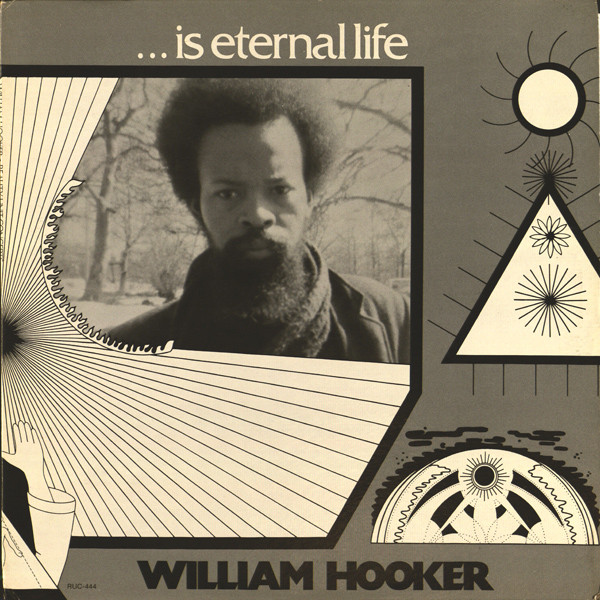

William Hooker – … Is Eternal Life (1977)

In my book, there are never enough records featuring drummers as bandleaders. Whenever they cross my path, they always end being serious love affairs. Few albums reach the mark achieved by Rashied Ali, Jerome Cooper, Billy Higgins, Art Blakey, Max Roach, Milford Graves, Sunny Murray, Jerome Cooper, and Famoudou Don Moye (among many others). There’s just something special which happens when drummers are at the helm, and William Hooker’s … Is Eternal Life, privately issued by in 1977 on his own Reality Unit Concepts, is no exception to the rule. It topped my want-list for more years than I care to count, finally, after a time, falling into my grateful hands.

Hooker, like a number of figures on this list, was a fixture within the 1970’s loft scene – a movement which saw players, pushing their creativity and sound to new heights, abandoned by their fan base from the previous decade. With few options, they banded together as a community, supporting each other and collaborating endlessly, opening artist runs spaces, often in the lofts where they lived (thus the name), and starting their own record labels. Some of it was politics. Some was just basic survival and need. As such, I’ve always thought of the loft era and its artists as the unsung forebearers of punk – political, filled with fire, self-actualizing, and decidedly DIY.

The beginnings of Hooker’s discography is a little bit like those of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor. He seems to have just appeared, fully formed. … Is Eternal Life, his first LP, is also the first on which name appears (at least as far as I know). It’s a hell of thing to achieve. It features two long percussion works which are stunning, with three additional, equally engrossing compositions – a trio with Mark Miller and David Murray, a duo with David S. Ware, and a final trio with Hasaan Dawkins and Les Goodson, both of whom seem to have faded from view sometime after the album was made.

Despite its works being realized by three or less players, .. Is Eternal Life has a huge sound – a writhing, conversant tapestry of rhythm and tone – fierce as it is thoughtful – the loft era at its best – completely blowing the doors off the movements of noise which would emerge over the decades down the road. It’s always confounded me that more people don’t talk about this one. It’s too good to be missed, though its obscurity may be a result of the fact that it’s never been easy to find – thus not easy to encounter or hear. Hooker’s still with us and kicking ass. Don’t miss it if you see his name on the bill.

William Hooker – … Is Eternal Life (1977)

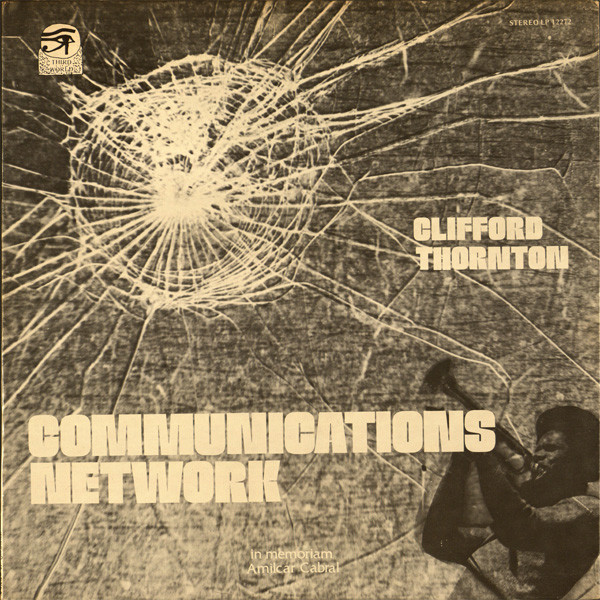

Clifford Thornton – Communications Network (1972)

Clifford Thornton is the perfect illustration of the the meeting point between radical politics and advanced music. He began his career playing with Sun Ra’s Arkestra, before, during the 60’s and 70’s, being drawn toward Black Nationalist movements through his friendship with Archie Shepp. There are references which imply that he subsequently became a minister of culture for the Black Panther Party, while France believed him politically dangerous enough to bar his entry. No small thing for a musician, but unfortunately something which damaged his career.

Thornton recorded prolifically with Shepp, runs his way all over the BYG Actuel series, and produced a number of recordings as a bandleader, all of which are remarkable. Communications Network is arguably my favorite. It was released on his own Third World Records, and is an incredible display of the diverse range in his abilities. The first side is a rising tide of sound and energy – free-jazz with the brakes removed, while the second is more delicate and restrained, laced with poetry by Jayne Cortez (Ornette Coleman’s wife). Stunning on every count.

Clifford Thornton – Festivals And Funerals Part One, from Communications Network (1972)

Clifford Thornton – Festivals And Funerals Part Two, from Communications Network (1972)

Abdul Wadud – By Myself (1977)

Abdul Wadud is an amazing figure in the history of free-jazz, and one of its few cello players. An artist of profound talent and insight, he began his career as a member of Ohio’s remarkable Black Unity Trio (who also deserve a spot on this list). He spent a number of years studying and playing Western Classical music, before going on to participate in dozens of noteworthy collaborations with members of The Black Artist Group, The AACM, and Frank Lowe, but remains grossly neglected, both by recordings and history. Like William Hooker, he was a central player during the loft era, but By Myself is the only record which finds him at the helm. As the title suggests, it’s a series of solo improvisations, filled with profound, vulnerable beauty. Privately released on his own label Bisharra, like so many other records on this list (and Thurston’s) it’s not easy to find, and rarely cheap.

There are very few albums of solo improvisations that achieve the heights of Wadud’s gesture on By Myself. It’s endlessly surprising and moving, with a range and ease which is astounding. A singular statement of individuality, drawing from the broad cultural legacies of the American diaspora. Sorrowful and melodic, to percussive, delving into remarkable tonal relationships and screeching fury, while threaded with flirtations with unplaceable pop melodies. By Myself is stunning – an incredibly honest record with few equivalents – flowed forth without artifice and nothing to prove. Pure unmediated creativity and art.

Abdul Wadud – Happiness, from By Myself (1977)

David Wertman – Kara Suite (1976)

David Wertman was in interesting figure during the loft era. One of the few white guys up on stage. People don’t talk about him much. He only made a small number of records under his own name, but what little he did packed a punch. He appears on the incredible The Universal Jazz Symphonette LP, issued by Billy Bang’s Anima Records in 1975, was a member of New Life Trio, whose lone LP on Mustevic Sound, Visions Of The Third Eye, has always been one of the great holy grails of free jazz, and plays bass on Steve Reid’s Rhythmatism and Odyssey Of The Oblong Square. I don’t remember how I came across it, but Wertman’s Kara Suite, issued by Charles Tyler’s AK-BA in 1976, has always been one of those records I can’t get enough of. Given that, other then Wertman, Tyler and Steve Reid are the album’s primary voices, I don’t look too far to figure out why.

Filled with an incredible energy and the kinds of tonal and structural interplay that set composers like Charles Mingus apart – like a freight train filled with a swarm of angry bees, this is one not be missed. It’s a shame that Wertman never got his due – an unmissable missing link within loft era jazz, and an essential entry in the discographies of Charles Tyler and Steve Reid. Definitely worth tracking down.

David Wertman – Kara, from Kara Suite (1976)

Maurice McIntyre – Humility In The Light Of Creator (1969)

Many years ago, during early encounters with Chicago’s Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), working my way through the catalog of their gestures, I found myself reading the back of Anthony Braxton’s Three Compositions Of New Jazz. The album was the forth in a serious of recordings by members of the collective, proceeded by Roscoe Mitchell’s – Sound, Joseph Jarman’s – Song For, and Muhal Richard Abrams’ – Levels And Degrees Of Light. Buried in its exploratory text, was the mention of a young tenor saxophonist, Maurice McIntyre, who Braxton believed to be the most important since John Coltrane.

Needless to say, my curiosity flared. How could a such player have escaped my awareness? Scratching the annals of history, I discovered that this mysterious player had been among the earliest members of the AACM, had played in the ensembles which recorded Mitchell’s Sound, and Abrams’ Levels And Degrees Of Light, before adding his own contribution to the AACM legacy with 1969’s Humility In The Light Of Creator. After a time, a copy eventually crossed my path. It was an opportunity I couln’t let pass. As I let the needle drop for the first time, a deep force blew from within. Braxton’s praise was well founded. As a player, McIntyre was profound.

Particularly compared to his peers in the AACM, Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre didn’t record much – a likely result of the fact that he struggled with a serious drug problem for much of his life. Including Humility In The Light Of Creator, he recorded two LPs for Delmark -1972’s Forces And Feelings is also stunning, appears on For Players Only, Leroy Jenkins’ brilliant effort with The Jazz Composer’s Orchestra, before slowly fading from view following a tiny scattering on Baystate, Black Saint, and Cadence toward the end of the 70s and beginning of the 80s.

It goes without saying that the history of 20th century music is threaded with loss and lost opportunity in the hands of drugs. I get it. The best art always comes from those who can completely open themselves and bear their souls, and doing such a thing often comes with great pain. But of all of them, the loss of the towering body of work that could have come to be in the hands of Kalaparusha – the man who Braxton thought was the most important player since John Coltrane, endlessly nags at my heart. He was an astounding force, player, and mind, something which anyone hearing Humility In The Light Of Creator will instantly know. Soulful, deep, complex, and intricate, bred with hard fought fire, it stands among the greatest creative efforts to ever emerge from the AACM (and that’s something, believe me). Tragically neglected and not hard to find, this one is as essential as the get.

Maurice McIntyre – Humility In The Light Of Creator (1969)

Noah Howard – The Black Ark (1972)

In the beginning, Noah Howard was at the heart of it all – one of the great talents within that NY 1960s scene which gave us those all those incredible records on ESP – the imprint which released the first two of his own. At the end of that decade, Howard, like most of the gifted members of his generation, left the United States for the greener pastures of France – a country which opened its arms, offering support, loving audiences, plenty of opportunities to play and record, and escape from the deep racism of the US. Unlike the rest, Howard never came back, a fact which probably contributed to his not being a household name. It certainly isn’t a consequence of any lacking in the work. Nearly everything he made is stunning.

Howard is one of those artists which leaves me struggling to pick a favorite LP. He was a hell of player, and, in addition to his work with Archie Shepp and Frank Wright, was pretty prolific as a bandleader during the 70s. Everything he touched is worthy of attention. But, 1972s The Black Ark, issued by Freedom, has always been especially close to my heart. The fucking ensemble is insane – Howard, Arthur Doyle, Earl Cross, Mohammed Ali, Juma Sultan, Sirone, and Leslie Waldron. It’s hard to get any better than that.

The Black Ark has it all. It’s one of those records which, in a single statement, captures all the potential and range of free jazz during this era – a hard blown conversation in rhythm and tone, which is at once forward thinking, intellectual, primal, complex, and rooted in the history jazz. It’s a swirling frenzy of emotion and ideas. It’s free jazz at its best, and nearly impossible to escape once the needle drops.

Noah Howard – Domiabra, from The Black Ark (1972)

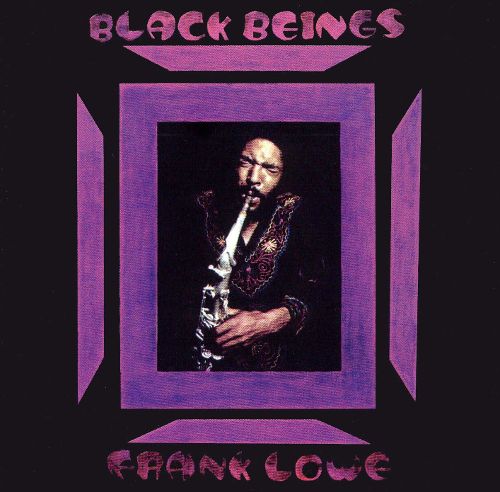

Frank Lowe – Black Beings (1973)

Frank Lowe is one of my favorite creative voices of all time. Duo Exchange – made with Rashied Ali and included within Thurston’s Top Ten, has been a record I’ve struggled to get off the turntable for all years I’ve owned it. That said, Black Beings, made during the same year, might be even closer to my heart. It’s a different kind of record – deeper, slower, more introspective and challenging.

Lowe made some great records with Alice Coltrane, Don Cherry, Noah Howard, Jerome Cooper, Kalaparusha, Billy Bang, and Joe McPhee, but almost all of that pales next to his work as a bandleader. Black Beings, with the Revolutionary Ensemble’s Vietnam, is one of the last great documents of free jazz to emerge on ESP, one of great catalogs and champions of this music. Made with an ensemble comprised of Lowe, Joseph Jarman, Rashid Sinan, Raymond Lee Cheng, and William Parker in his recording debut, the album is a beast – pure gold. Soulful and filled with fire, intricacy, remarkable interplay and sophistication, it’s an album which set tinder for the coming loft-era. Not only one of my favorite records of the 1970s, but within the entire incredible ESP catalog. Any free jazz collection without will be forever plagued by a giant hole.

Frank Lowe – Black Beings (1973)

Horace Tapscott Conducting The Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra – The Call (1978)

Geography weighs heavily on the history of jazz. Following the Second World War, New York looms large – often the sole occupant within our depth of field. A clear vision the West Coast can be hard to find, but it offers incredibly exciting territories of sound – containing artists like Bobby Bradford, John Carter, and Horace Tapscott, who are so surprising and wonderful they should force us to question everything we know or have been told. Their obscurity is confounding.

The Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra was formed by Tapscott in 1961, but The Call, self released on his Nimbus West Records in 1978, was the fist presentation of their work in recorded form, and only the second (after a decade long gap) where Tapscott appears as a leader. It’s a remarkable piece of work – one of the great gestures of big band free jazz from this era, presenting a very different notion of this music than the one put forth by figures like Sun Ra. Rich, incredibly intelligent, it rocks and writhes in heavy grooves, shifting fluidly between dissonance, melodic interplay and outright free improvisation, all sliced apart by Tapscott’s amazing piano lines. This is one of those records which shatters the boundaries of geography and or notions of history. Unquestionably one to get.

Horace Tapscott Conducting The Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra – The Call (1978)

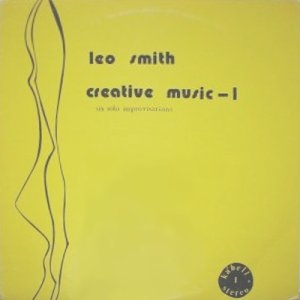

(Wadada) Leo Smith – Creative Music – 1 (Six Solo Improvisations) (1972)

My love affair with the music of Wadada Leo Smith is long, deep, and old. In mind mind, he’s the most important composer working anywhere today. He’s our Ellington or our Mingus. Every year he seems to get better and better, unleashing incredible, singular compositions upon the world. While I could have easily included any number of his more recent efforts, particularity 2012’s Ten Freedom Summers, which is fucking masterpiece, somehow Smith’s music has transcended the simple category of free jazz, and thus I cast my eye to his earlier days – where it all began, his debut LP, Creative Music – 1 (Six Solo Improvisations), from 1972.

By the time Creative Music appeared, Smith had already threaded his remarkable voice through some of the great recorded efforts in free jazz – Anthony Braxton’s 3 Compositions Of New Jazz, as well as Braxton’s two LPs for BYG Actuel – B-X0 NO-47A, and This Time…, Muhal Richard Abrams’ Young At Heart / Wise In Time Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre’s Humility In The Light Of Creator (featured above), and Brigitte Fontaine and Art Ensemble Of Chicago’s incredible Comme À La Radio. Creative Music is slightly free standing in his output. Smith’s next release as a bandleader wouldn’t appear until the end of the decade. Given all the other incredible efforts he was part of – work with Marion Brown, Clifford Thornton, Leroy Jenkins, Frank Lowe, and Roscoe Mitchell, as well as co-founding the Creative Construction Company and New Dalta Ahkri, it’s not surprising. He had his hands full.

Among my favorite pockets within the history of free jazz, is one its most challenging ventures – solo improvisations. These gestures, most notable among members of the AACM, push an artist to the brink of their skills and expose their towering talents. The solo improvisation offers its creator nothing to respond to beyond the depths of self. It exposes and offers no shelter. Artists we venture toward it deserve profound respect. Creative Music – 1 (Six Solo Improvisations) is one such case. Privately released on his imprint Kabell, it seems the album was not well received upon its release, and may have prompted Smith to write notes (8 pieces). The text directly answers criticisms it faced, and offers an analysis of each of its compositions. If people didn’t like it, I don’t know what the fuck they were thinking – it’s a masterpiece.

Creative Music, being remarkably singular, defies easy categorization. Smith’s sensibility is thrilling and deeply personal. Nothing is held back – an open door to his intellect and emotional depths – ever ambitious, attempting to break from tradition and venture into new territory. The distinct character of Smith’s music is striking. The language is his own, but flows from a deep history of African American experience and sonic legacy. Rather than following the progressive thread of his peers, he distills thousands of years of music and culture, and then begins again. In his hands, sound is profoundly beautiful thing.

Creative Music is an incredible display of restrained notes which mold themselves into an unmistakable sorrow. Despite the already exposing nature of its form, Smith placed himself at further risk by broadening his sonic pallet into sounds beyond his chosen instrument (the trumpet) – lacing it with compositions for percussion and flute. The result is an incredible balanced, multi-layered discourse. The rattle of “tiny instruments,” the sputter of the flute, the bleat of the trumpet, though sparse and restrained, becomes explosive whole. An unmistakably towering achievement. Unfortunately I can’t find any samples of it online, so you’ll just have to track it down and listen for yourself.

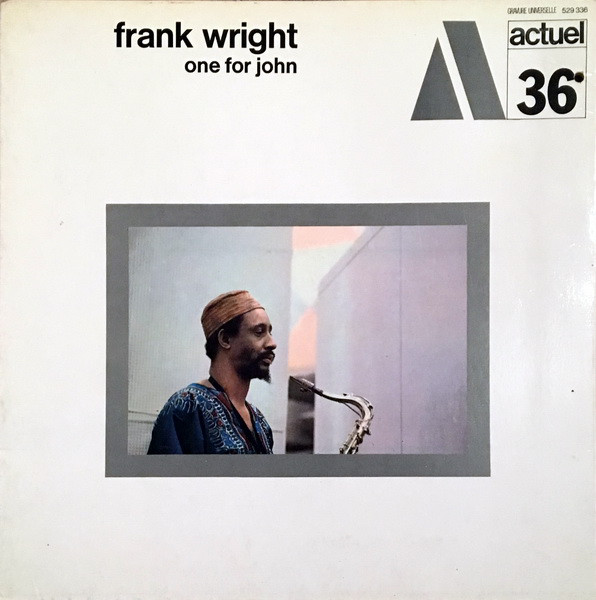

Frank Wright – One For John (1970)

Frank Wright, of these eighteen incredible artists, is only one of two who I’ve allowed to overlap with Thurston’s list. That should tell you something. He can’t be skipped or missed. Wright, like Noah Howard, with whom he collaborated, was one of the great talents within that NY 1960s ESP scene, the imprint which also release the first two efforts as a bandleader, before, like so many others, leaving the United States for the greener pastures of Europe. He also remained there for much of his life, releasing a brilliant string of albums under his own name, and founding Center Of The World with Alan Silva, Bobby Few, and Muhammad Ali, all of whom he worked extensively in different incarnations over the years.

One For John, released in 1970 by BYG Actuel, has always been among my favorite LPs by both Wright, as well as within the series – among the most iconic in the entire history of free jazz. Thus, in the simplest sense, it represents a perfect opportunity to nod to both. Made with a stellar ensemble comprised of Wright, Noah Howard, Muhammad Ali, and Bobby Few, it’s hard to imagine these sessions could have ever failed or become anything other than what they are – absolutely stunning.

Intricate, writhing, filled anger and pure emotion bound to a deep sense of interplay and artistry, in my view it’s one of the definitive effort within the collaborations which unfolded within France at the end of the 60s and the outset of the 70s. Liberation in every sense of the word.

Frank Wright – China, from One For John (1970)

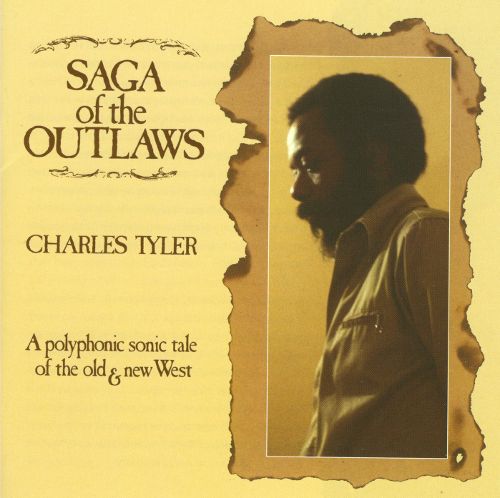

Charles Tyler – Saga Of The Outlaws (1978)

Charles Tyler has long been one of those artists who I’ll chatter endlessly about to anyone who will listen. One of the great voices of free jazz, who all to many people forget. Tyler began within Albert Ayler’s iconic ensembles, playing on both Bells and Spirits Rejoice, before recording two brilliant LPs – the self-titled Charles Tyler Ensemble, and Eastern Man Alone, for ESP during the second half the 60s, working steadily, within his own ensembles and those of others, until his death in 1992.

Those aware of Tyler tend to veer toward his ESP records, those issued on his own AK-BA imprint, or his playing with Steve Reid, all too often overlooking 1978’s Saga of the Outlaws, which, at least to my ear, is among his best. Recorded with an ensemble comprised of longtime Sun Ra Arkestra member John Ore, Ronnie Boykins, and Steve Reid, you better know it’s gonna be good.

Saga of the Outlaws is a fucking thrill in listening from top to bottom. There isn’t a dull moment within. It sets you anxiously on the end of your seat – stretched way way out, trying to figure where the hell its going and what the hell is being said. I can say with certain surety, after all the years I’ve owned it, and an uncountable number of listens, that I still haven’t figured it out. It puts you out of your depth, just were I want to be. One of the unsung greats, by a brilliant artist all too often looked. It’s among the cheapest and most readily avaible of the records on this list and an absolute must.

Charles Tyler – Saga Of The Outlaws (1978)

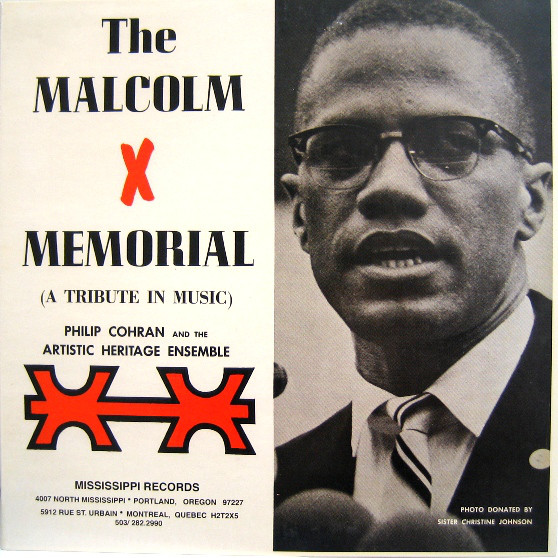

Philip Cohran & The Artistic Heritage Ensemble – The Malcolm X Memorial (A Tribute In Music) (1970)

For a lot of ears, Philip Cohran & The Artistic Heritage Ensemble’s The Malcolm X Memorial (A Tribute In Music), privately issued by Cohran in 1970, might offer a bone of contention by calling it free jazz. But, a big part of the definition of free jazz is founded on the notion of freedom, rather than a specific sound, and, in addition to the fact that Cohran was there from the start, freedom is what this record is all about.

For the bulk of his long career, Kelan Phil Cohran was a significant contributor to the history of jazz, while remaining one of its most neglected figures. He began his career as a member of the Sun Ra Arkestra – featuring on 6 of their early LPs, but, ehen the band left Chicago, he stayed behind, becoming, with Muhal Richard Abrams, Jodie Christian, and Steve McCall, one of the four founding members of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians – arguably the most important collective of musicians ever established.

Much of the neglect that Cohran has suffered was self initiated. He was always a fiercely principled and independent musician. Differences lead to his early departure from the AACM, after which he began The Artistic Heritage Ensemble. The band self-released two LPs – On The Beach and The Malcolm X Memorial and three 45s during the 70’s. None reached their rightful audiences – owing to Cohran’s justifiable resistance to working with the white run record industry and distribution system.

I’m such a big fan of Cohran’s output that it’s nearly impossible to pick a favorite, but The Malcolm X Memorial hits me like a brick every time I let needle drop – founded, not unlike Sun Ra’s, on vision of Black Nationalism which spliced the contemporary with the ancient world as much as the long history of black music. It’s all there – a big band sound taken to the outer reaches – a seething sea of ideas, honking and angry – another vision of what the avant-garde could be.

The Malcolm X Memorial is brilliant, wonderful, overwhelming, and not quite like anything I can call to mind. It makes my heart race with every listen. A towering achievement which everyone should own. Call it what you will, but if free jazz is about freedom, this is what it is.

Philip Cohran & The Artistic Heritage Ensemble – Malcolm X, from The Malcolm X Memorial (A Tribute In Music) (1970)

John Carter – Castles Of Ghana (1986)

When I discovered this record a few years back, it was like getting hit in the face by a brick. John Carter was a sinfully neglected powerhouse. His energy was overwhelming, as a composer he was profound. Unlike many of his contemporaries who fell into obscurity, Carter languished in it for his entire career. His name is not only lost, it was almost never known – yet another victim of the tragic little attention paid to artists on the West Coast. Almost everything Carter put his hand to is worthy of attention, but Castles Of Ghana is beyond belief. It’s a high-water mark in avant-garde Jazz, and easily one of the most exciting records made in any genre during the 80’s. It’s so neglected, I almost never see copies, but when I do they’re in dollar bins. No one seems to know better. It’s an off kilter, big-band free jazz of the finest order, but of rarely seen sort. Rather than the freestanding atonality, it utilizes dissonance and tension drawn from tonal and rhythmic friction between multiple players. It’s composition is complex, takes the reins of Ellington and Mingus, then pushes to outer-space. It defies definition, and persists into unknown territory without neglecting its musicological legacy. I can’t begin to recommend this album enough.

John Carter – Castles Of Ghana, from Castles Of Ghana (1986)

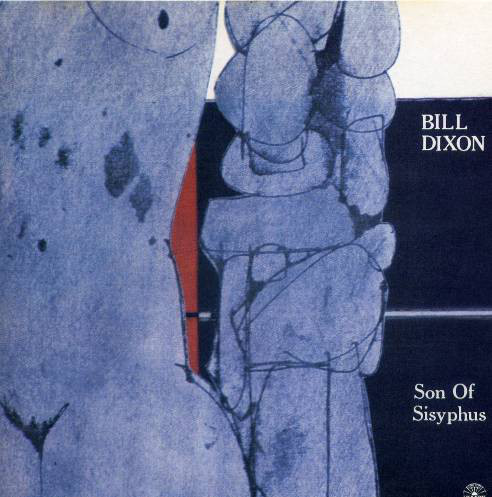

Bill Dixon – Son Of Sisyphus (1990)

Bill Dixon is one of my favorite composers, and Son Of Sisyphus might rank among my top ten records of all time. It’s absolutely astounding. Released in 1990, it’s the latest entry on this list – standing outside of time. Dixon was a radical figure during the 1960’s – angry, political, and one of his generation’s greatest minds. As a composer he ranks among the best of any era. During the late 60’s his anti-capitalist views and concerns regarding the relationship between race and cultural production, motivated him to remove himself from the music world. He spent the next decade composing and recording in isolation. He didn’t waste a moment. When he returned he was skills as a composer were towering. Dixon only produced a thin discography. Most of his records were released to unresponsive audiences during the 80’s, but everything he touched was gold. His efforts stand as some of the most singular gestures in the history of Jazz, and are even more striking for the context in which they were placed. It’s impossible to convey how important he was.

Son Of Sisyphus is steeped in restraint and sorrow. It is at once abstract and laced with palpable human emotion. Notes scatter and scrape against each other and disappear across tangible distance. The album is filled with a profound sense of space. It’s completely singular – unlike anything I can call to mind. It feels as though it has breathed itself into existence with no effort on the part of its composer. It captures a profound depth of emotion and the heights of intellect. Not only one the best records of the 90s, but one of the best of all time.

-Bradford Bailey

Bill Dixon – Schema Vi-88, from Son Of Sisyphus (1990)

This is an absolutely killer list. So much to digest here… Even in the age of the internet recommendations this deep are hard to find. Any more lists of this sort would be welcome.

LikeLike