Peter Orlovsky, William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Alan Ansen, Paul Bowles, Gregory Corso, and Ian Somerville, Tangiers 1961

I first encountered the name Paul Bowles when I was 12, while reading Ted Morgan’s remarkably comprehensive biography of William S. Burroughs, Literary Outlaw. The book had been a point of conversation in my family since its publication a couple of years earlier. The woman who was married to my uncle at the time was the daughter of Kells Elvins, one of Burroughs’ closest friends, and featured on a number of its pages. I wondered what all the chatter was about, and dove in. The book was a turning point in my life, connecting me to strategies for negotiating a world I already despised. From its pages flowed remarkable figures who broke from a restrictive society and lived beautiful lives of independence and dissent. Their voices wrapped themselves around my heart and became my guides. I vowed to read everything I could. One of the most intriguing was Paul Bowles, whom Burroughs had encountered in Morocco at the beginning of his expatriation there in 1954.

Paul Bowles / Darius Milhaud – Concerto For Two Pianos, Winds And Percussion (1950)

At the dawn of the 50’s Bowles became a famous author. His first novel, The Sheltering Sky, was a resounding success. Because he spent the bulk of his life dissociated from the outside world, Bowles is generally regarded as a singular and free standing figure. During his early years, he was remarkably connected to the leading intellectual lights of his era. He began his creative life as a poet and was published along side many of the most noted Surrealists. During the 20’s, he abandoned his efforts as a writer to become a composer, gaining a high level of recognition in that field. The 1950 Columbia release, shared with Darius Milhaud, of his Concerto For Two Pianos, Winds And Percussion, is worth your time if you can track it down. As is the excellent collection of his writings on music, pictured below. He was a close friend of Aaron Copland, and the two traveled extensively together. He spent the late 20’s and much of the 30’s in Paris and Berlin, and was part of Gertrude Stein’s inner circle. He was closely associated with Tristan Tzara, Stephen Spender, and Christopher Isherwood, among others, and collaborated with Orson Welles and Tennessee Williams.

Paul Bowles – On Music (2003)

When he returned to New York in 1938, he met the writer Jane Auer, and despite each having a preference for their own sex, the two were married shortly after. Though her bibliography is thin, Jane Bowles was one of the greatest literary voices of her generation. Her work has suffered neglect over the decades. I take this opportunity to direct you toward her. I can’t recommend her words enough. Throughout The Second World War, the couple shared a house in Brooklyn Heights with W. H. Auden, Carson McCullers, and Benjamin Britten, and marks Bowles’ return to writing. In 1947 he resolved to return to Morocco, where he had traveled with Aaron Copland during the 30’s. The couple never returned.

Paul and Jane Bowles

Bowles’ love for North African culture is well noted. It threads itself through his books, stories, friendships, and the way he lived his life for the next 50 years. Having traveled through Morocco, I can understand why he never left. It’s an incredible place, where time folds into itself. The ancient world nestles within the present, whispering in its ear. The country’s sites and sounds have no equivalent.

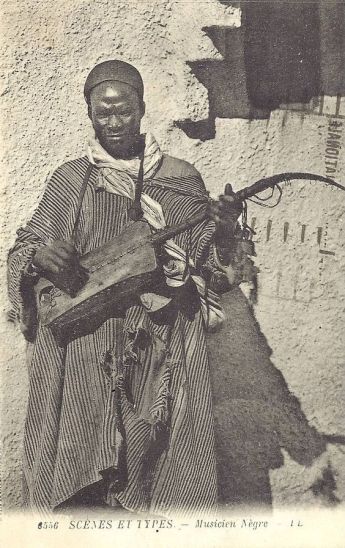

Street Musicians in Marrakesh, 1954

An often neglected attribute of many progressive forms of Western Classical music during the later part of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, was a relationship to the folk idioms of Europe and beyond. Rimsky Korsakov, Stravinsky, Tchaikovsky, Vaughan Williams, Bartok, and others, all collected folk songs, and incorporated their elements into compositions. This was a paradigm of music that Bowles first entered. His initial draw to Morocco, during his years as a composer, was for its music. What he heard laid the foundation for a life long love.

Bowles at the Piano, 1930’s

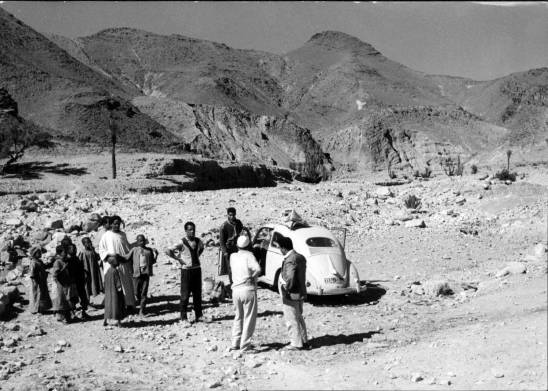

Prior to the 1950’s, during which attitudes toward anthropological practices shifted, and new opportunities developed with the introduction of portable reel to reel tape recorders, most “collecting” of traditional and folk musics occurred through writing and notation. Though Bowles’ love for Moroccan music was noted upon his arrival in that country, I expected the new context of the 50’s encouraged him to begin his attempts to champion the beautiful sounds which filled his world. During July of 1959, a month prior to the beginning of Alan Lomax’s iconic field recording journey in the America South, Bowles set off on a six month expedition in the dessert to document and record the musical traditions of Morocco. Like many field recordings of the era, they were commissioned by The Library of Congress, with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation, intending to preserve important cultural traditions, and not conceived for commercial release. During the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s, The Library of Congress issued a number of recordings from its archives, but I can tell you first hand, they’re not easy to find. I suspect that the releases were intended for cultural institutions and libraries, rather than music fans, and rarely reached general circulation. Traversing the country in a Volkswagen Bug and armed with an Ampex reel to reel, Bowles recorded 60 hours of music, compiling 250 artifacts of Moroccan culture. Upon his return, these recording went to Washington, and gathered dust for more than a decade.

It’s likely that Bowles recorded with the Ampex 600 (top left)

In 1972 a selection of Bowles’ recordings were issued by The Library of Congress across a two LP set. Those four sides contain twenty two tracks, which account for less than ten percent of the trip’s total. I heard about about these recordings when I was in high-school, but given their rarity, it took me a number of years to track them down. For those of us who collect field recordings of ethnic folk musics, Bowles’ are the stuff of legend. They’re regarded so highly that most collectors place them along side the recordings of the most prominent figures in the field – Hugh Tracy, John Levey, Alan Lomax, Peter Crossley-Holland, David Lewiston, Charles Duvelle and Pierre Toureille.

Paul Bowles – Music of Morocco (1972)

The musical traditions of Morocco are incredibly rich and broad. They grow from ancient traditions of Islamic music fed and altered by the African continent bellow. They’re deeply geographic, often locked within the lands from which they sprang. As Bowles traveled the country, he captured the sounds of the Berber and Riffian cultures, with diverse street, Gnawa, cafe, and trance musics. Swirling reed flutes, ghimbris, lutes, drums, castanets, and voices, bridge across centuries and diverse cultures. They rattle and rise into ecstatic heights. Simply put, they’re as wonderful as can be.

Gnawa Street Musicans, Early 20th Century

I own a a fairly large stack of LPs which capture traditional Moroccan music. There is no question that Bowles’ is the best of the lot. Because this is often music made in public, most recordings are drowned in ambient sounds and space. Bowles’ recordings for the Library of Congress bring the musicians rushing into the room. Their depth, detail, and presence is striking. I’m often overwhelmed by the feeling that they were recorded yesterday.

Paul Bowles – Music of Morocco (2016)

A few days ago I noticed an announcement in my feed. Dust to Digital is re-issuing these recordings in an expanded edition on April 1st. For those who haven’t encountered Dust to Digital before, it’s worth taking note. Since its incarnation in 2003, the label has been issuing a constant stream of amazing lost or neglected recordings from around the world. They caught my eye with their first release Goodbye, Babylon, a sprawling six CD wooden box set (stuffed with raw cotton), containing some of the best recordings of rural American Folk music I’ve ever heard. Their subsequent box of lost John Fahey recordings sealed the deal. Though their projects are far too ambitious to realize in any other form, and it slightly goes against the nature of their name, I daydream that they’ll start issuing their projects on LP. From what I can tell, their realization of Bowles’ recordings is a fairly faithful (though remastered) representation of the original. The track listing seems more or less the same, but it contributes another eight unheard tracks. It also offers expanded liner notes, an introduction by Lee Ranaldo, and Bowles own travel notes. Whether you’re down with digital or not, I strongly recommend you give it a spin. These recordings are absolutely mind blowing, and not to be missed. Perhaps down the road, given that there are over 200 recordings remaining in the archive, the label will give us more.

As a slightly expanded celebration of the release, I thought I’d share these little seen pictures of Bowles’ recording journey. I hope you enjoy.

Bowles’ Hand Drawn Map for the Trip.

-Bradford Bailey